-

-

Chapter 2:

The Fine Art of Sadomasochism

-

Although they were created within the context of a masculine game design culture by guys who notoriously liked to posture and show off, the original Doom games aren’t very difficult. Let’s face it: gamers just weren’t that skilled back in the early 1990s, the first-person shooter genre had barely begun to exist before the Doom engine came along, and not every computer even had a mouse. If they’d made Doom much more challenging, it wouldn’t have enjoyed the immense popularity that it did, because few people would have been equipped to play it yet. Although some games (both classic and modern) are designed to be difficult, the sorts of niche skillsets that are required to achieve true mastery are generally not the stuff of commercial games anyway. Instead, they tend to be the domain of—you guessed it—modding communities.

In any game community with any staying power at all, challenge creep is inevitable and begins immediately. As soon as the base game has been conquered, people will start to look for more difficult ways to challenge themselves with it, a need that gives birth to speedrunning scenes and similar subcommunities—bonus points if you have to detonate a rocket in your own face to cross the finish line in record time. For Doom, which was one of the first games that was editable using easily accessible tools, creating new maps became another available outlet for players to find the challenge they were looking for. Highly skilled players become mappers, creating maps that scratch their particular itch or push their skills even further. The best of these creations become recognized as the go-to for challenge-seekers. The new releases become milestones, new mountains that every challenge-seeking player wants to climb. Meanwhile, the best players keep getting better, and the ceiling rises. This isn’t just a side effect of the existence of modding communities; it’s a part of why modding communities exist.

The best players keep getting better, and the ceiling rises. This isn’t just a side effect of the existence of modding communities; it’s a part of why modding communities exist

Ultimate Doom’s more limited set of monsters, weapons, and items results in simpler core gameplay with a somewhat lower skill ceiling than Doom 2 has, which is why the challenge community tends to revolve around Doom 2. That doesn’t mean that nobody seeks to make challenging maps for the first game; Id Software’s own Thy Flesh Consumed is one of the great early examples. But Doom 2 added a ton of combat components, most notably several mid-tier enemies with attacks that require more specialized skills to evade, and these components have become the basic building blocks of most challenge-oriented mapping. It didn’t take long after the release of Doom 2 before the biggest and most influential of the early challenge mapsets saw the light of day.

-

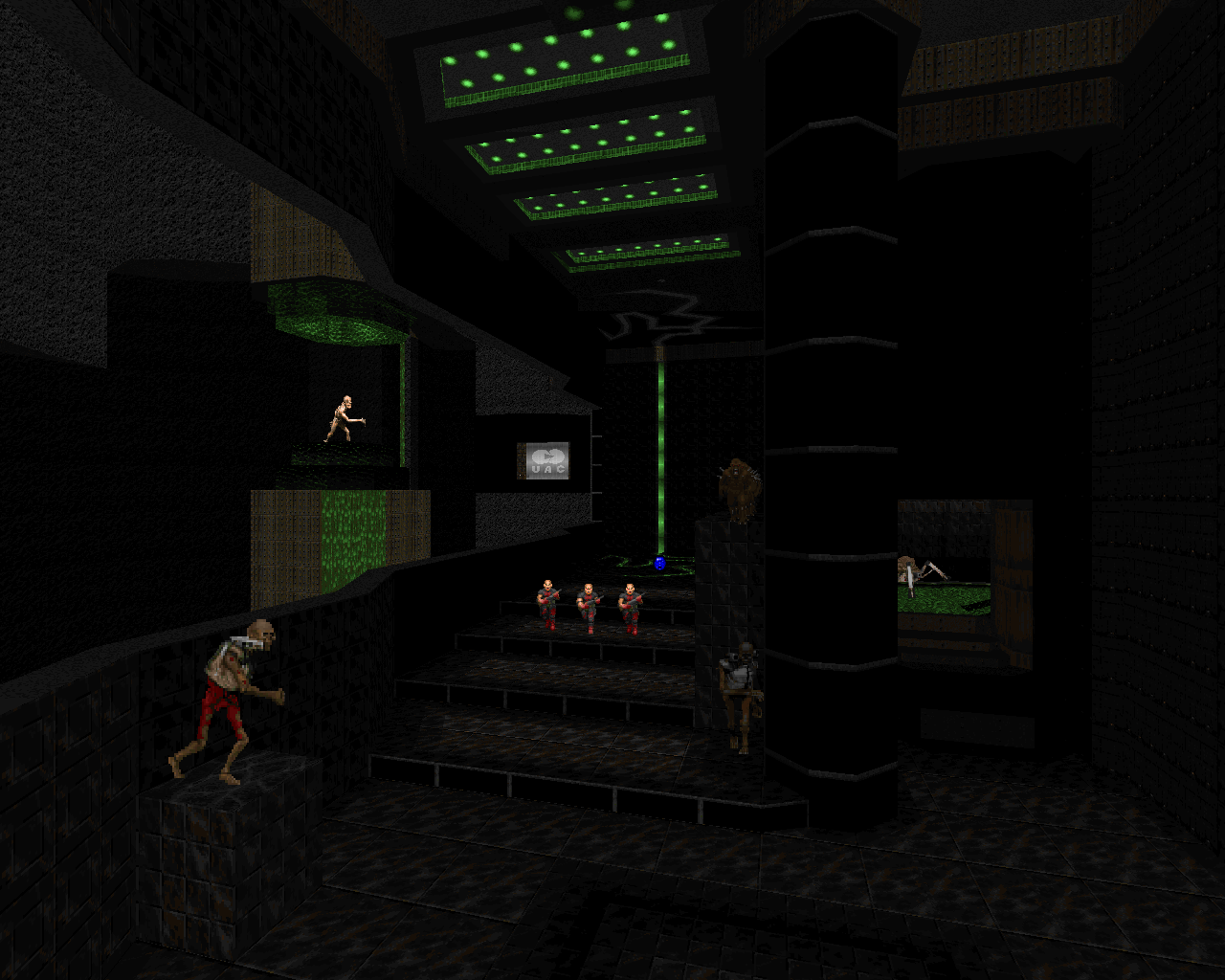

The Plutonia Experiment - Dario and Milo Casali (1996)

The Plutonia Experiment - Dario and Milo Casali (1996)

Skip the Small Talk

Plutonia is one of those megawads that tells you what you’re in for right off the bat. The original Doom introduces monsters slowly and deliberately; Doom 2 is a little freer in its usage, but still maintains a strong sense of increasing challenge and threat hierarchy. Many Doom mappers savor the gradual introductions of monster species, even decades later. Plutonia, on the other hand, doesn’t waste any time throwing you into the midst of deadly combat. The first monsters you encounter in “Congo” (map 01) are either shotgunners or chaingunners, rather than basic Former Humans or Imps. Dive a little way into the map, and you’ll quickly discover that a significant number of its 46 monsters on Ultra-Violence are Mancubi and Revenants—and not individual ones framed as easy introductory miniboss fights, but small groups of them placed to be threatening. There’s a Pain Elemental playing a support role as well, but the most striking appearances are the two Arch-Viles. Even though both are optional—and indeed, the whole map offers opportunities for evading rather than engaging—placing them in map 01 is an extremely clear message as to the megawad’s philosophy: if you’re not seriously prepared for a fight, then you’d best get your kicks elsewhere. It cuts to the chase because Milo wasn’t interested in fiddling with gameplay that he didn’t think was fun, but it’s also a good communication tactic that’s been used in many challenge mapsets since, perhaps most recognizably with the Cyberdemon that lords over map 01 of Ancient Aliens.

Monster placement is the key to all of Plutonia’s level design. The megawad focuses almost entirely on the threatening placement of small numbers of monsters, heavily emphasizing the more powerful monster types, though it goes fairly light on the boss monsters. Chaingunners, Revenants, and Arch-Viles are the holy trinity of Plutonia combat, as they are the most immediately threatening monsters in the bestiary and the ones that have the greatest effect on the player’s movement decisions. Mancubi, Arachnotrons, Pain Elementals, and harasser Cacodemons typically fill in the supporting roles, with groups of shotgunners providing periodic bursts of glass cannon uncertainty to keep you on your toes. Imps mainly exist to give you the occasional quick pop of satisfaction; Hell Knights, Barons, and Pinkies are used sparingly and are there to intimidate and hog space, demanding that you slot them into your list of priorities in order to gain more freedom of movement. At the risk of stating the obvious, most small-scale challenge mapping over the years has followed a very similar mold for overall monster placement, simply because it works extremely well and is very hard to improve upon.

The first map makes Plutonia's philosophy clear: if you’re not seriously prepared for a fight, then you’d best get your kicks elsewhere

Hierarchical monster presentation is hardly the only design element that Plutonia eschews for the sake of focusing on the combat. The architecture is plain and utilitarian, with aesthetic beauty and detail so utterly deemphasized that many of the map themes are simply ripped directly from Doom 2 and given new shapes as appropriate for the fights at hand. Though most ‘90s mapping is pretty austere out of necessity, one can easily compare Plutonia to TNT: Evilution, its sister megawad in the commercial release of Final Doom. Whereas Evilution places a fair bit of importance on environmental design in order to make the maps feel more like real places, Plutonia heavily emphasizes abstraction, tailoring the shapes of architecture to fit the flow of combat.

The map layouts and progression are designed to be compact, semi-open, and relatively flowy, as opposed to being a bunch of discrete areas strung together. Having different sections of a map connect fluidly helps many of the monsters to be threatening, as you are typically pressured from multiple angles, but it also allows the mappers to focus on pacing. The result is that each map is both fast-moving and very bloody, like a perpetually moving brawl. The player is put in the position of struggling to overcome the number of challenges in play at once and is frequently forced to move around—either retreating back into territory that’s still dangerous or advancing into areas with new threats—due to either being placed at a sudden disadvantage (e.g., with an ambush) or having space denied to them (by groups of threatening monsters or by damaging floors). Even the very beginning of a map is sometimes hostile, with “hot starts” that force you to react to oncoming monsters as soon as you spawn in the map instead of giving you space to breathe and collect yourself before plunging in.

The Casali brothers laid so much groundwork that all combat-oriented mapping has been a series of footnotes to Plutonia

Although the brawl-like core design is fairly consistent across the megawad, Plutonia is more experimental with its combat at times and brought in some very distinct innovations that, like the core combat, have been echoed in many other challenge mapsets over the years. The perpetually resurrecting chaingunners in “The Twilight” (map 15) were perhaps the first major example of monsters being treated as pure mechanics, with no pretense of being living beings in an ecosystem, as odd as it may sound—and perhaps the first case of combat design that was deliberately belligerent, specifically designed to be alarming, frustrating, and “unfair” while at the same time being a well-reasoned, intentional choice that serves the goals of the level design. Similarly, the iconic “Hunted” (map 11), which teases you with a mob of Arch-Viles and then disperses them all over what is effectively a large hedge maze and expects you to find your way through, is perhaps the first combat-oriented concept map.

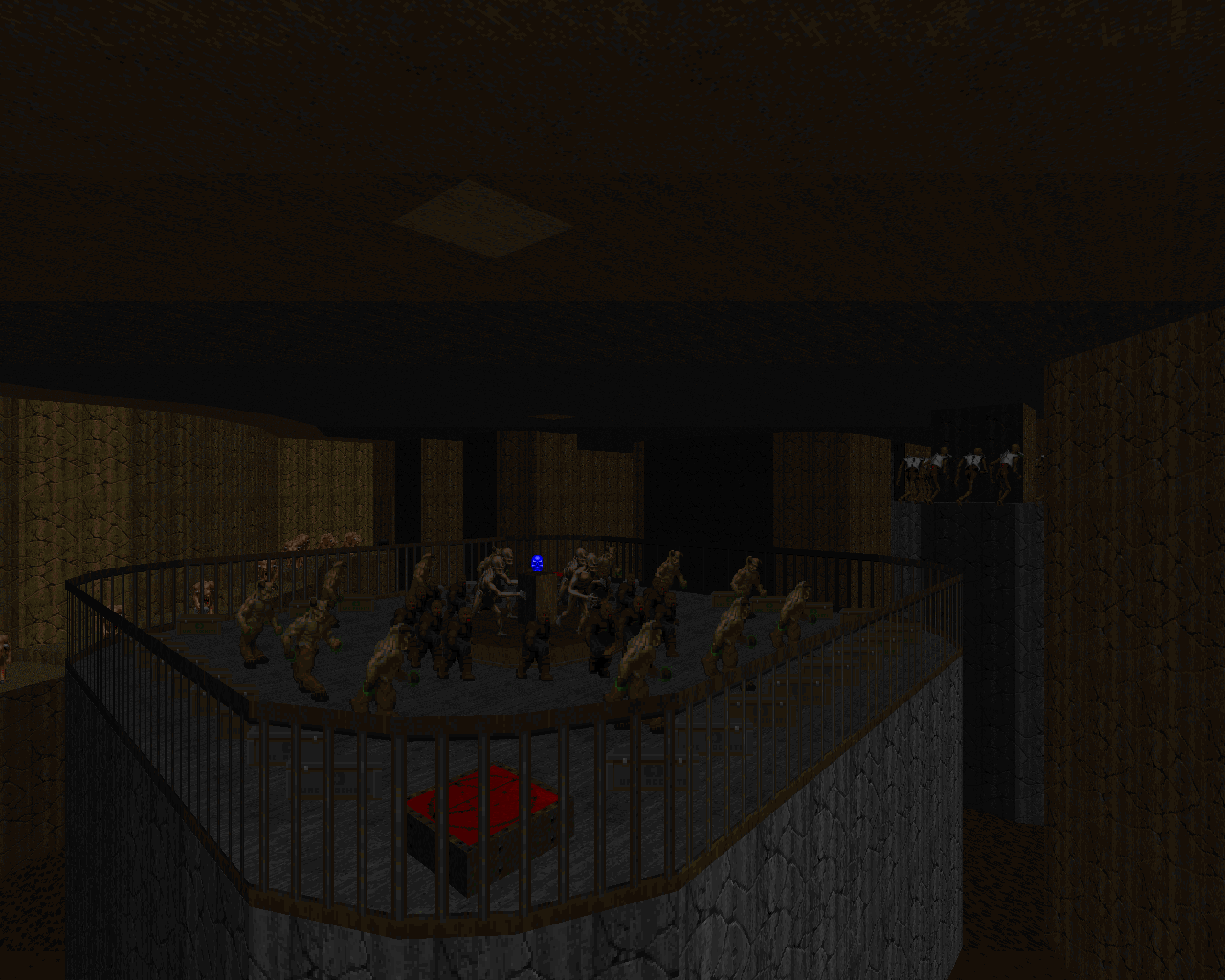

And then there’s “Go 2 It” (map 32), which stands out as the most brutal map in the set, a first foray into extremely heavy, monster-dense combat with lethal floods of monsters at every turn and more Cyberdemons than appear in the entire rest of the megawad combined. With its massive threat levels and complete lack of any space that appears remotely safe, this BFG- and rocket-heavy map is designed to confuse and intimidate a less experienced player (i.e., almost everyone playing Doom in 1996) into thinking that it’s simply impossible—but in the end, it plays out as something of a puzzle, where you have to find the best way to gain a foothold and approach the rest of the challenges from there. This type of gameplay paved the way for monster-dense challenge mapsets like Hell Revealed and, eventually, the modern hardcore scene, and it has come to be known most commonly by the evocative but somewhat vague term “slaughter.” “Go 2 It” is also very sensibly placed as an optional super-secret map, and the idea that secret maps are the ideal slots for the most intense and monster-heavy maps in a megawad has become fairly common in later years.

Plutonia was the first major release that focused entirely on combat, and that hyper-focused dedication is what makes it so successful

Plutonia was the first major release that focused entirely on combat, and that hyper-focused dedication is what makes it so successful. The two mappers kept playing and refining until they had worked out all the fundamentals, exploring a full range of combat styles and concepts and examining the uses of each monster in the bestiary as mechanical components, ignoring most other aspects of design in their quest to create the ideal form. Although the Casalis’ work leaves plenty of room for improvement, it’s fair to say that they laid so much groundwork that there wasn’t a whole lot left to lay, and that all combat-oriented mapping has been a series of footnotes to Plutonia.

-

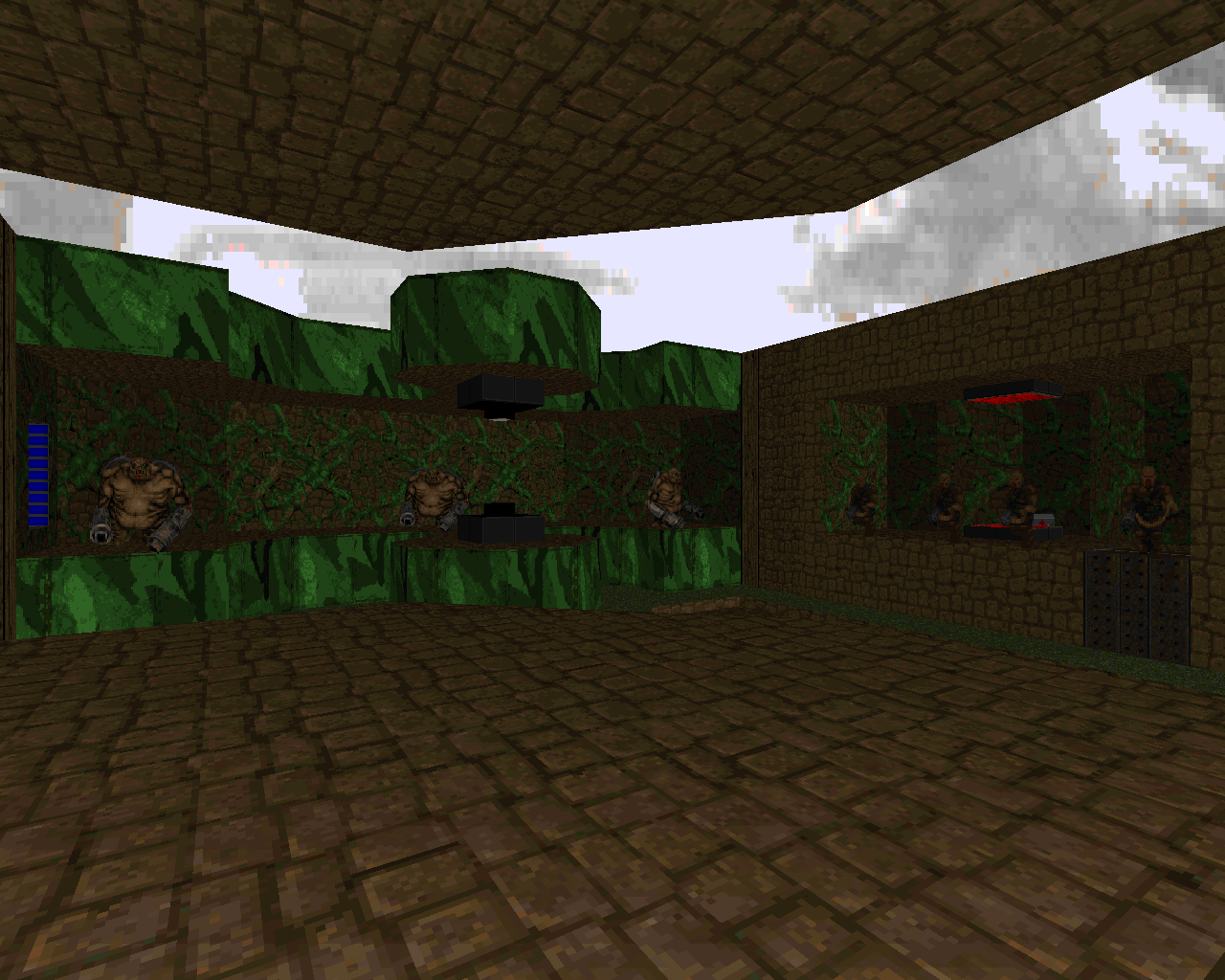

Hell Revealed - Yonatan Donner and Haggay Niv (1997)

Hell Revealed - Yonatan Donner and Haggay Niv (1997)

Siege Engines

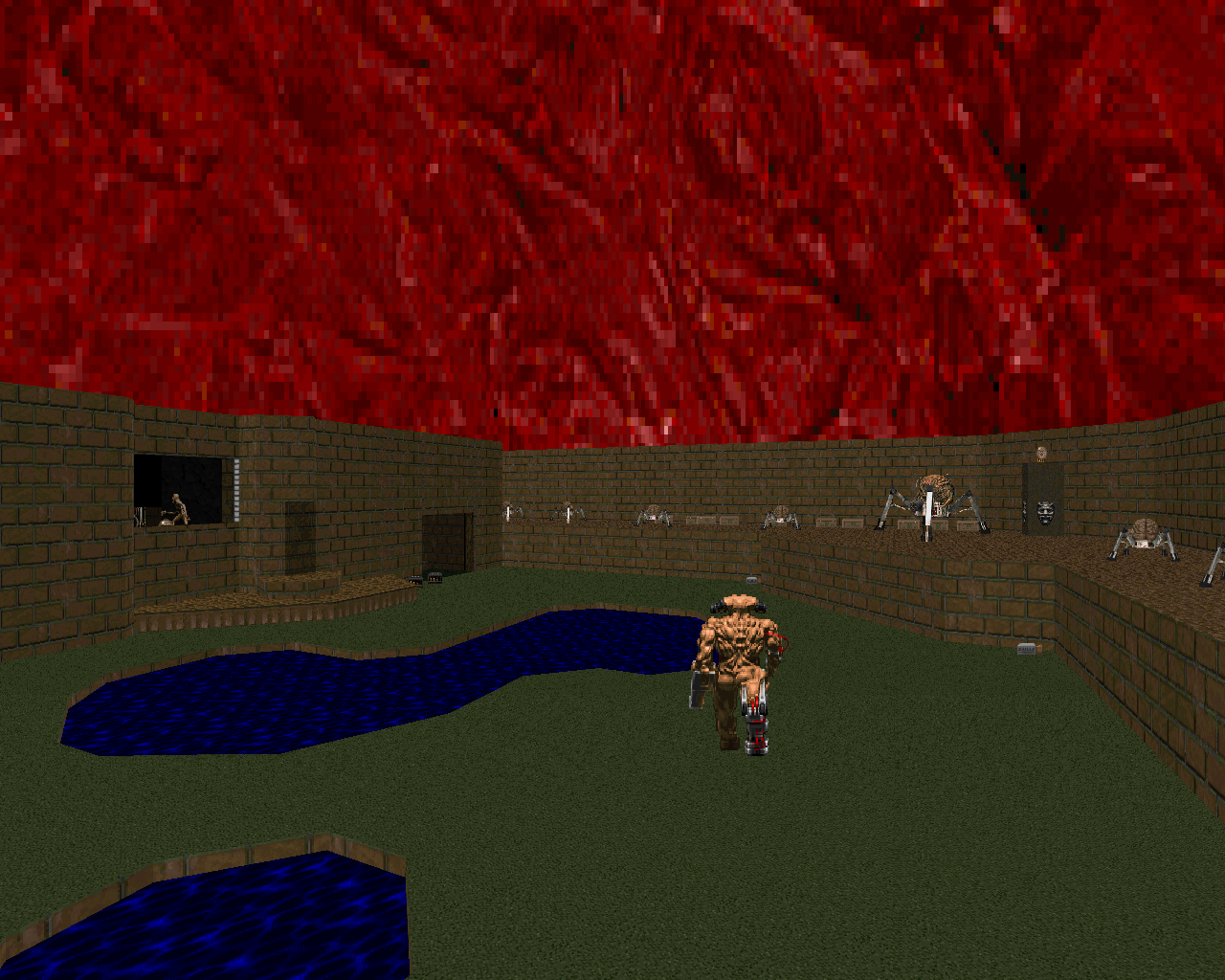

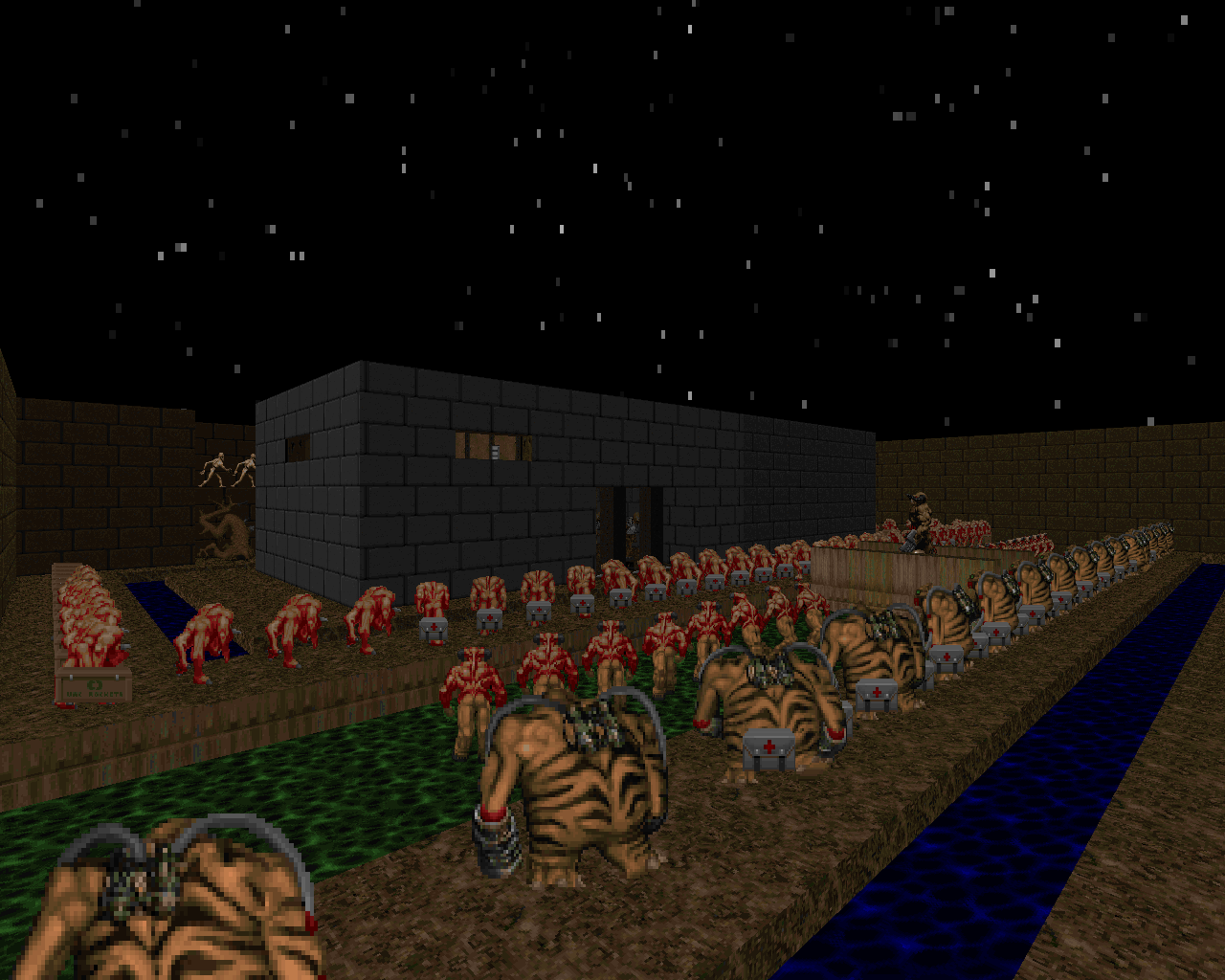

Following just a year after Plutonia was released as part of Final Doom, Hell Revealed asks the next obvious question with regard to challenge mapping: What if there were lots more monsters? Like, lots more? Perhaps using “Go 2 It” as a springboard, Donner and Niv created an entire megawad’s worth of maps defined by monster density, which was highly novel at the time and was essentially built-in advertising for the idea that Hell Revealed was the most challenging set of maps ever made (which it most likely was).

It drew competitive players like flies, particularly since it was one of the first mapsets designed with the express purpose of being speedrun—and it still has more speed demos than any other PWAD to this day. This immense popularity among speedrunners was itself a major source of influence, and challenge mapping, demo compatibility, and speedrun-friendly design have gone hand in hand for decades as a result. It’s one of the major reasons that challenge maps have almost exclusively been created for vanilla and Boom map formats until very recently (as in, literally this year), as ZDoom-based ports have too many engine quirks to support competitive demo compatibility.

Hell Revealed asks the next obvious question with regard to challenge mapping: What if there were lots more monsters?

Donner and Niv were new to mapping when they began the project, and the first half of the megawad has had relatively little stylistic influence—though it still has its share of demos. Most of the iconic maps are in the latter half, and it’s these maps that established the signature gameplay style that Hell Revealed and its followers in subsequent years are remembered for. Somewhat similar in style to “Go 2 It,” these maps are designed as rudimentary combat puzzles where developing a strategy and gaining a foothold are the key to succeeding. The gameplay style is based around dense blocks of entrenched enemies alongside individual boss-tier monsters; the former exert large amounts of pressure by limiting player movement and flooding the playable space with projectile attacks, while the latter exert zones of control that force them to become key components of the player’s strategy, both as threats to be outmaneuvered/dispatched and as tools for infighting. With the whole playable space overshadowed by these threats, players are compelled to consider the enemy force as a whole rather than as individual monsters, essentially becoming one-person siege engines. The goal of each large battle is to find a crack in the defenses, some way to carve out a position and then dismantle the whole works from within.

These types of setups allow for a dual approach. If you find the right strategy, you can work quickly to eliminate the enemies, which means that solid routing and planning will give you advantages in a speedrun; on the other hand, the entrenched nature of the enemy force means that you can work more slowly and methodically if you need to. This flexibility, combined with full support for all difficulty settings, made it a good go-to mapset for players trying to develop their skills—but its Ultra-Violence was still seen as the ultimate challenge at the time, a yardstick by which other mapsets were measured. Though Hell Revealed’s siege warfare is less dynamic than the combat styles you’ll find in modern challenge maps, and has largely fallen out of favor, it served as a cornerstone of big fight design for many years to come—particularly in megawads like Alien Vendetta and Kama Sutra that sought to combine big, impressive visuals with the spectacle of large-scale combat.

Players are compelled to consider the enemy force as a whole rather than as individual monsters, essentially becoming one-person siege engines

-

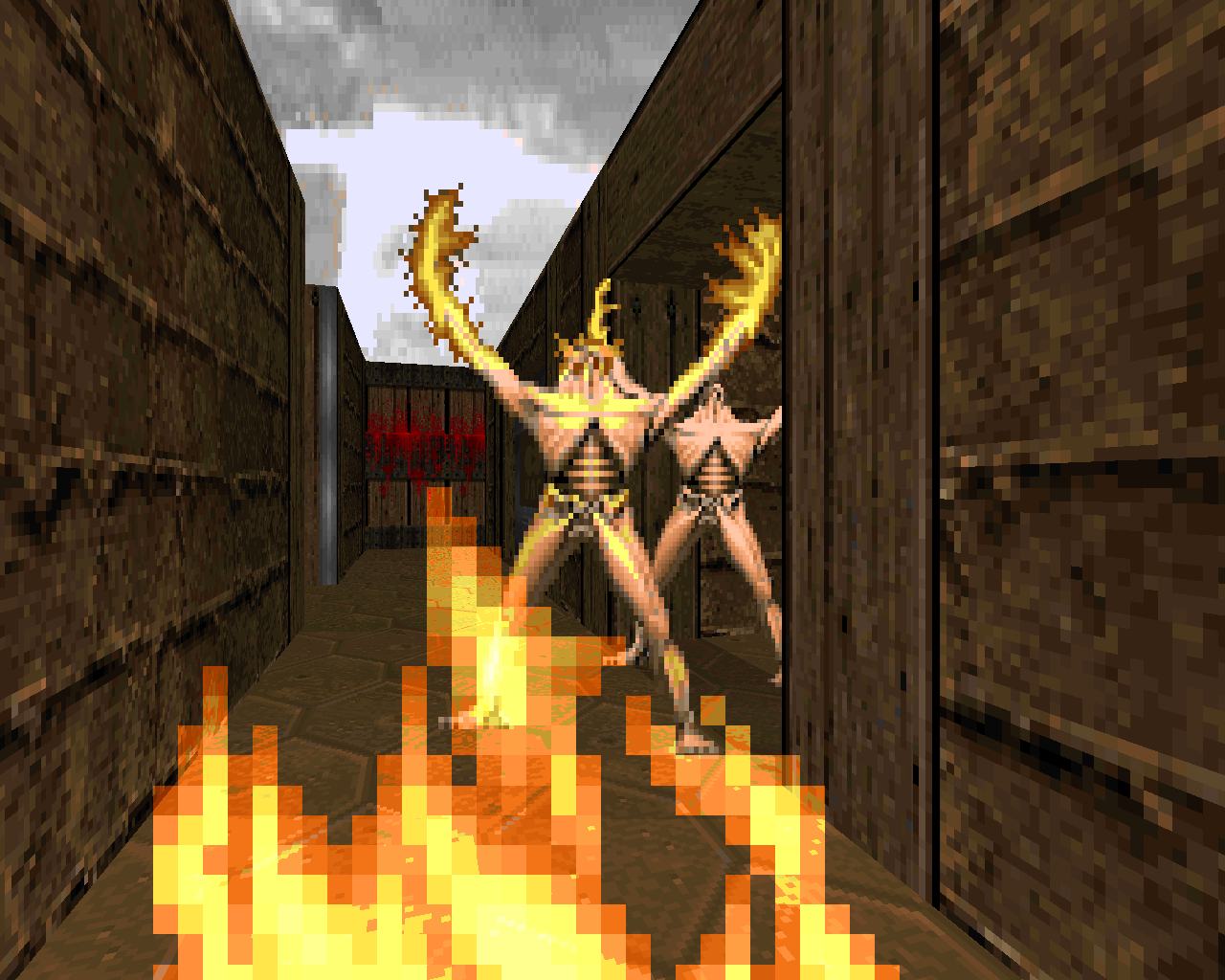

Chord G and Chord 3 - Malcolm Sailor (1999/2000)

Chord G and Chord 3 - Malcolm Sailor (1999/2000)

The Puzzle Box

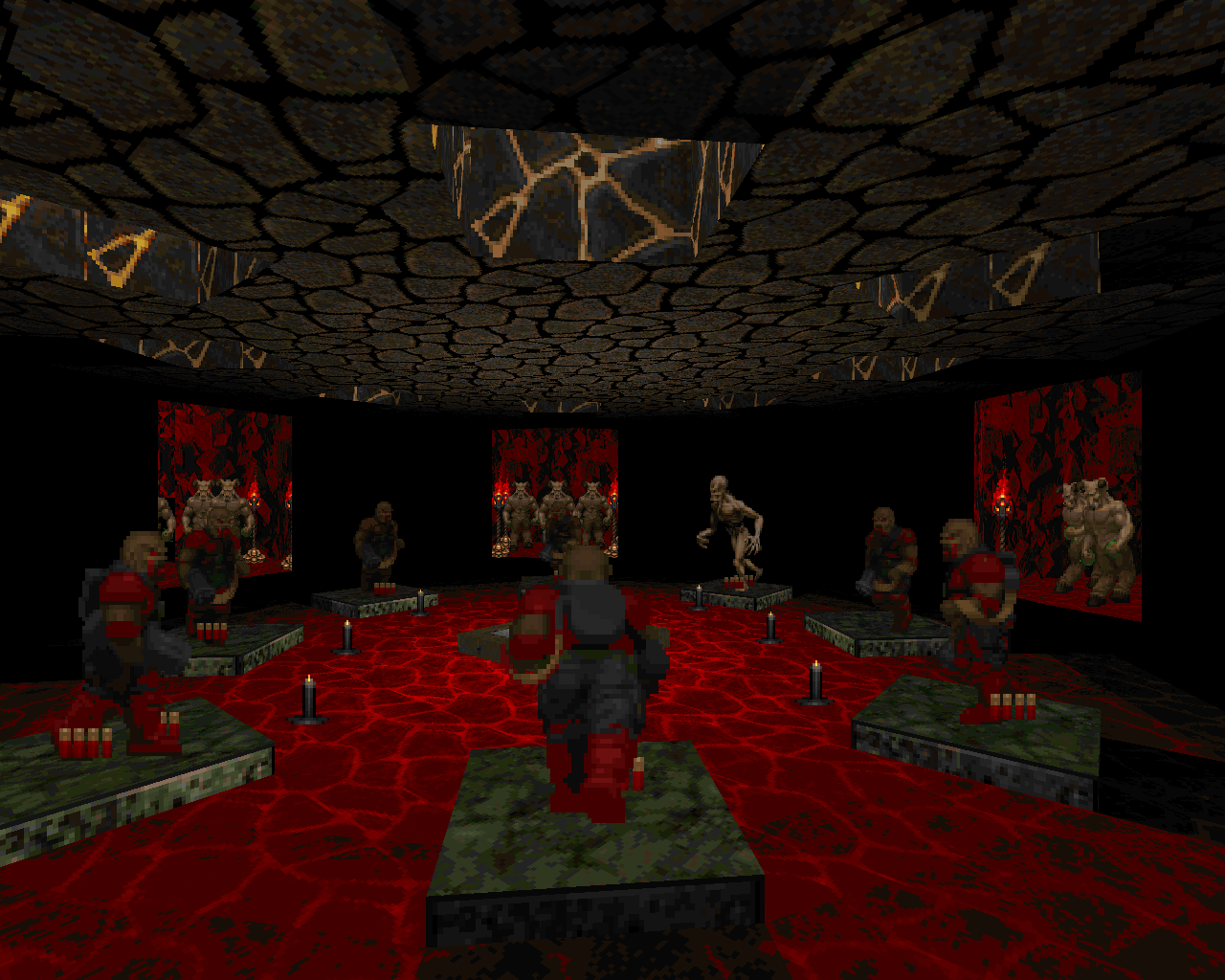

The five-map Chord series takes the idea of “combat puzzles” to the next level, particularly in its last two entries, Chord G and Chord 3. Essentially ignoring the large-scale siege concept of Hell Revealed, Malcolm Sailor’s hardcore maps take ideas more directly from Plutonia but spin them into true nightmares that take a great deal of thought and skill just to survive, let alone conquer.

The Chord maps deploy a combination of tight spaces, heavy-duty monsters, and resource scarcity, which together turn seemingly simple map layouts with around 100 monsters total into a grueling, relentless fight to stay one step ahead of your enemies. Ammo and other items are allotted in such a way that you have barely enough to keep going, forcing you to leave enemies at your flank and push on to find the next breadcrumb cache as the map fills up with threats around you, while saving your hard-won shells and rockets to take out the top-priority threats or the ones that you absolutely have to remove in order to clear a path. High-threat enemies like Revenants and Arch-Viles demand a high level of attention in close quarters, while Barons and Hell Knights serve as space dominators, requiring too much time and ammo to dispatch immediately but taking up so much room that outmaneuvering them becomes critical.

The Chord series take a combination of tight spaces, heavy-duty monsters, and resource scarcity to turn seemingly simple map layouts into a grueling, relentless fight

With such tight, intense design, every decision can make or break your run through the map, and the level of strategy required is highly appealing to methodical puzzle-solvers and speedrunners alike. In Chord 3 in particular, getting to the exit alive is only half the challenge; the only way to clear all the enemies is with a smart mix of infighting and Berserk-enabled melee combat to conserve ammo. If there was any one development that foreshadowed the highly advanced, macro-strategic combat of the modern hardcore scene, it wasn’t Hell Revealed with its intimidating swarms—it was Chord with its vicious pressure-cooker gameplay and riddles to disassemble one piece at a time.