-

-

Chapter 4:

The Great Synthesis, Part 1

-

So there you have it: throughout the 1990s, the formation of clashing mapping ideologies, a community already dividing based on the priorities of different players. Plutonia’s gameplay was beloved by more challenge-oriented players, but it wasn’t particularly interested in presentation, beauty, or narrative and thus had little to offer anyone else. Hell Revealed was impressive but was viewed as completely inaccessible for many players. Eternal Doom was steeped in atmosphere and adventure, but drove a lot of people crazy with its obscure progressions and switch hunting. Does any of this sound familiar?

But what if you could have your cake and eat it too? The idea that you can simultaneously have smooth, tough gameplay alongside strong aesthetics or mood must seem glaringly obvious from a 2019 perspective, but like all good ideas, somebody actually had to do it before it became obvious that it could be done. Dichotomies always have their logical limitations, but there have to be mistakes, mixed feelings, great works that leave something to be desired, itches that need to be scratched, before someone can come along and offer the best of both worlds. Simply put, you can’t have something that offers the excitement of both Hell Revealed and Eternal Doom before Hell Revealed and Eternal Doom exist; the skills needed to create it aren’t apparent yet.

The idea that you can have smooth gameplay alongside strong aesthetics seems obvious today, but like with all good ideas, somebody actually had to do it first

By the turn of the millennium, many players and mappers had moved on from Doom to Quake and other more modern games. Some of the greatest early mappers, including Iikka Keranen, Matthias Worch, and Dario Casali, had graduated to careers in commercial game design. Many of the major post-Requiem mappers—Anders Johnsen, Anthony Soto, Brad Spencer, Lee Szymanski, Kim Andre Malde, and others—had gotten together to create a team megawad out of Johnsen’s struggling one-man project, after which most of them would drift away from Doom. The twilight of the game’s odd little mapping community had always seemed like it would inevitably arrive sooner or later, and with the coming of the new millennium and the biggest of the “Doom killer” games themselves becoming obsolete, it must have felt more imminent than ever.

In other words, it was about time for somebody to create the most influential PWAD of all time.

-

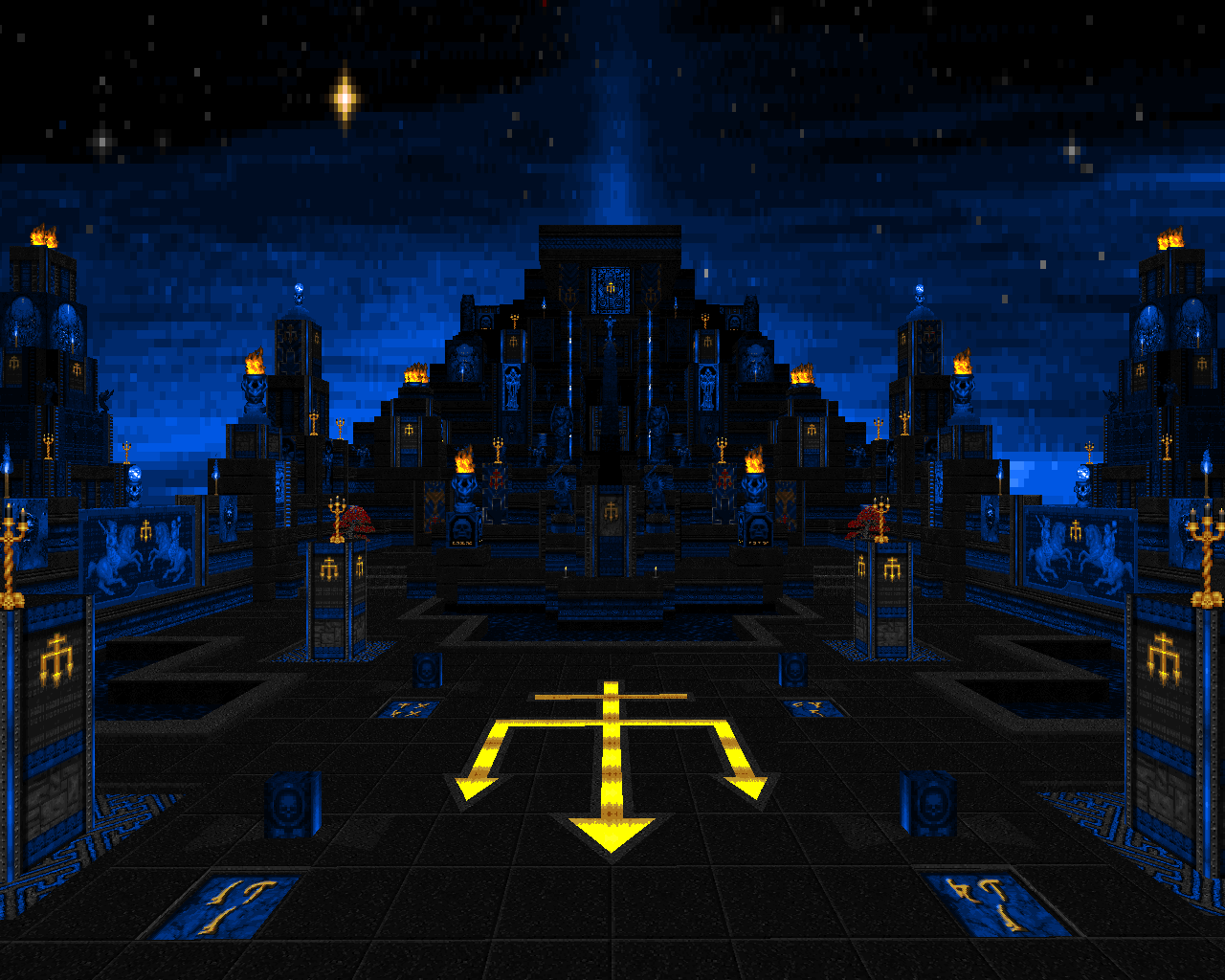

Alien Vendetta - Various (2001)

Alien Vendetta - Various (2001)

Fiat Lux

That Johnsen-led megawad was Alien Vendetta, and although it was recognized as a great work in its own time, it has gradually come to be cemented as the closest thing Doom mapping has to a holy scripture. In 10 Years of Doom, Cyb referred to it as the “last great classical megawad,” a description that’s been paraphrased many times in the years since. With all the changes happening in the early to mid-2000s, it probably looked like the last of its kind, and in some ways it may have been. But for my part, I’ve often thought of it as the first great modern megawad instead. Both labels are equally true; Alien Vendetta was the turning point for Doom mapping, the crossover from the understated philosophies and ambitions of the 1990s to the mapping community as we know it today.

Even now, it’s a bit hard to pin down exactly what was important about the megawad, because the things it accomplished were so broad and easy to take for granted. It’s not so much that people take specific ideas or techniques from it, as they do with Plutonia and Eternal Doom, but rather that it has given the community its entire conception of what Doom mapping is and should be. It’s the canvas upon which most subsequent Doom mapping has been painted, the framework to which later mappers have added drywall, electricity, and plumbing—particularly when it comes to maps made in the more classic vanilla and Boom formats, but not exclusively. As I’ve already implied, Alien Vendetta represents a synthesis between the aesthetic and artistic ideals of adventure mapping and the satisfying combat of challenge mapping; there’s certainly more to it than that, but it’s worth looking at how it accomplishes that synthesis before we get into more complex philosophy.

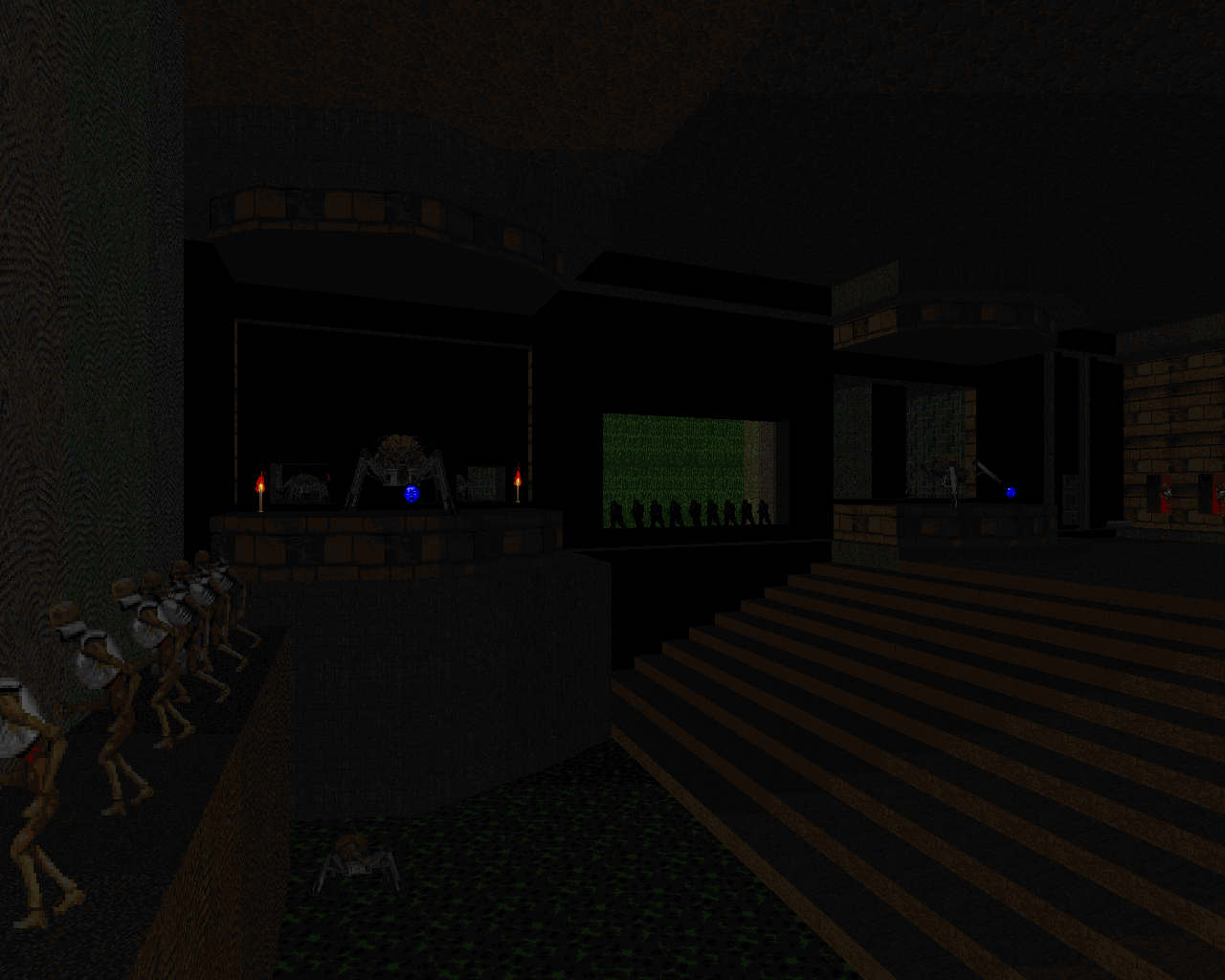

Alien Vendetta primarily styles its combat after Hell Revealed, but with many refinements and a different target audience. Monsters are frequently presented as a flood rushing at the player, but the overall flow of combat is often tempered with more dynamic, Plutonia-like moments, relying on the strategic placement of more dangerous monsters. The toughest maps—typically Johnsen’s—use siege combat similar to the later Hell Revealed maps, which offered a good combination of intimidation and accessibility, genuine threat and the feeling of epic intensity. The monster placement in AV also tends to emphasize presentation wherever it’s possible to do so without diminishing the combat; rather than simply being clumped into units like in Hell Revealed or treated as completely individual like in Plutonia, monsters tend to be placed more organically—snipers perched on aesthetic arrays of crates, turreted enemies given attractive perches with positions that play to the architecture, and a general eye toward how monsters look as an arrangement in relation to each other. Among the best examples of the megawad’s combat presentation is “Hillside Siege” (map 06), which sets up enemies so that you feel like a one-person Normandy invasion force, pushing forward against ranks of enemies with advantageous tactical positions but with enough maneuverability to avoid being bogged down by them.

Alien Vendetta may have looked like the “last great classical megawad,” but I’ve often thought of it as the first great modern megawad

The overall difficulty level is aimed at being enjoyable for strong players, but it’s intentionally lower than Hell Revealed in most cases. Even the background information in the textfile makes it clear that the mappers put a great deal of thought into how AV related to Hell Revealed and how its intended player base had shifted thanks to careful moderation. AV is meant to be enjoyed by a wider audience, to find a more moderate middle ground between people who play for intensity and people who play for simpler sorts of fun. At the same time, its toughest maps match or even surpass Hell Revealed, which creates a sense of climactic escalation at various points in the overall progression and makes victory feel more hard-won. The most obvious comparison between the two megawads is Johnsen’s “Dark Dome” (map 26), which is a direct homage to the most famous map in Hell Revealed, “Post Mortem” (HR map 24). Each map is the epitome of siege warfare in its respective megawad, but “Dark Dome” is more streamlined, more dense, more challenging, and all around more impressive than its predecessor.

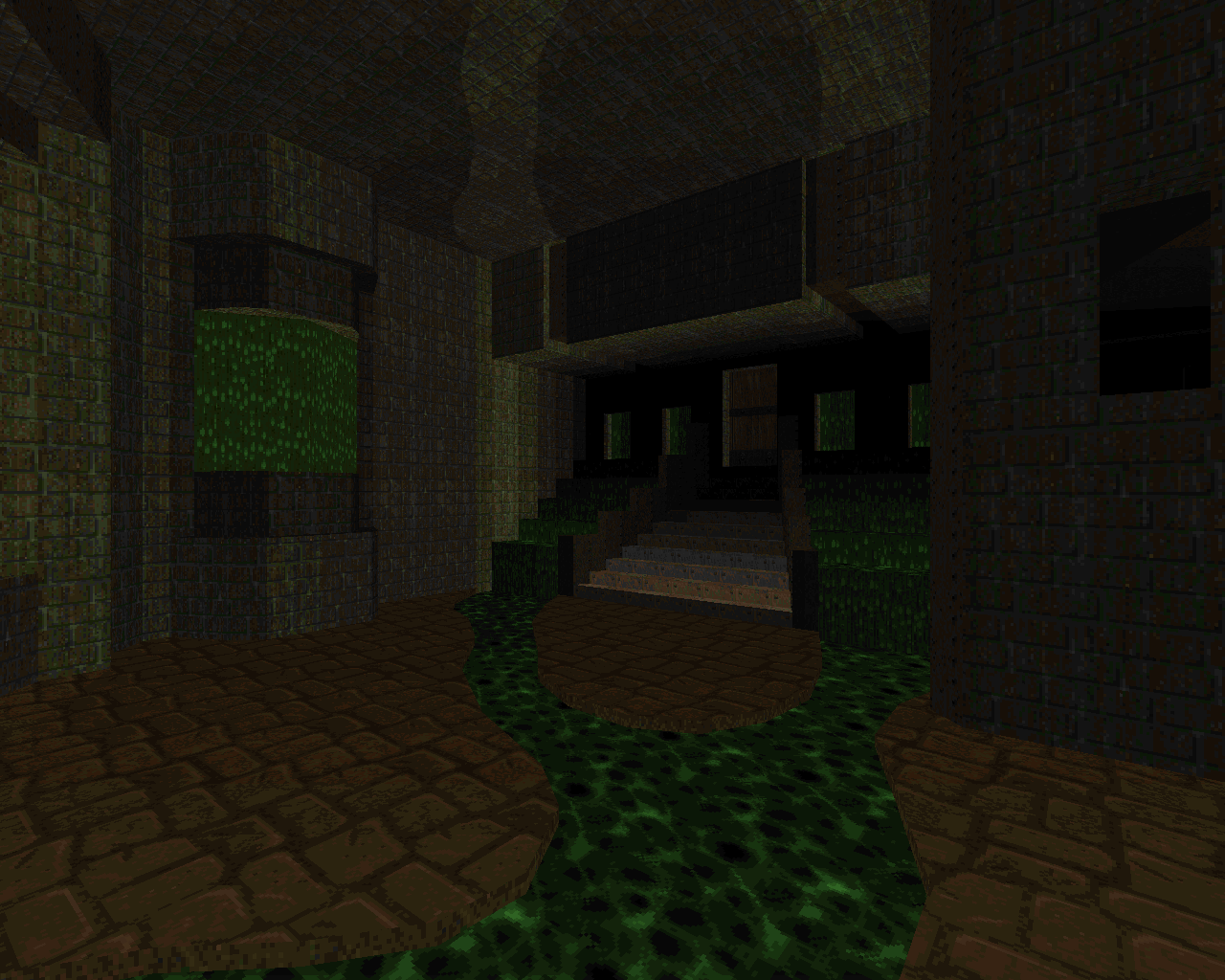

Alongside its tough, engaging combat, Alien Vendetta adds in a number of adventure elements that make the setting more interesting and give players more of a feeling of being part of a story, as in Eternal Doom. A number of maps feature realistic sector-art details, like the ship in the harbor in “Cargo Depot” (map 03) and the train track that runs between that map and “Seclusion” (map 04), giving them a sense of connection to each other. “Beast Island” (map 08) tosses you into a wasteland and tasks you with making the journey from a ruined village to a seaside castle, and “Nemesis” (map 11) takes you on an even grander adventure through a honeycomb of caverns and a series of towering island fortresses high above the water. There are even some cool storytelling tricks like the hanged Imps in “Fire Walk With Me” (map 29). But although they’re an important part of the level design, the story and setting details are kept out of the player’s way or are limited to areas with few monsters, and many occur outside of the playable space, which keeps them from interfering with combat.

Alien Vendetta was the turning point for Doom mapping, the crossover from the understated philosophies and ambitions of the 1990s to the mapping community as we know it today

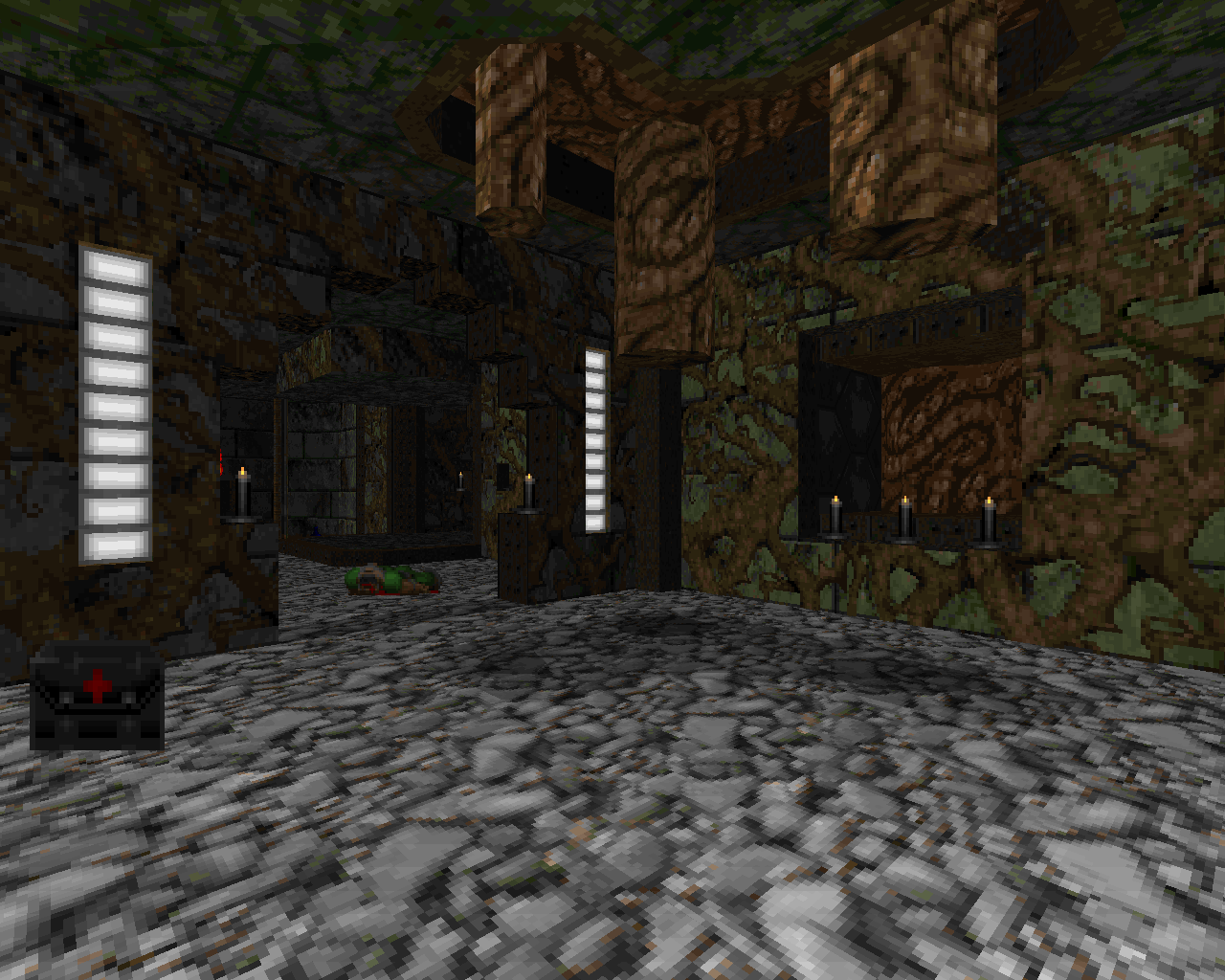

The level of architectural detailing in many AV maps is significant; the mappers considered aesthetic beauty to be important, and on the whole, it was among the most detailed releases that had existed up to that point (perhaps only surpassed by the GothicDM series, which was itself pretty infamous for sacrificing gameplay in the name of aesthetics). Rooms and architectural facades are shaped in as complex a way as possible within vanilla limits, frequently relying on regular pillars and ceiling cutouts in the vein of Eternal Doom, but Alien Vendetta also begins to work a lot more with inset trim, such as metal borders around the interiors of windows (and other methods of creating a frame within a frame), as well as corner trim on buildings. Much of its detail comes in stacked tiers—stair-like cutouts forming the tops of arched doorways, windows that appear semi-rounded, and nested cutouts in ceilings and walls. “One Flew Over the Caco’s Nest” (map 21) is one of the best examples of the megawad’s emphasis on detailing, as it manages to pack an incredible amount into its tighter spaces, both regularized detailing such as insets and unique details such as cords of flesh dangling from the ceiling. Detailing of roughly similar complexity had been done before in a handful of cases, including the Chord series and The Darkening E2, but Alien Vendetta was the first to apply these sorts of high aesthetic standards across an entire megawad, and it really left an impression. Its combination of specific detail tropes was so effective and easily reusable that it has become the foundation for much of modern detailing, and is still used today in a much more refined form.

Alien Vendetta also firmly established the Doom community’s modern lighting aesthetic, though it borrowed individual elements of it from GothicDM 2, Eternal Doom, the Chord series, and 99 Ways to Die. It turns out that this type of consistently detailed lighting was possible in the vanilla engine all along, and you can see it in AV as early as the opening view of map 01. Alien Vendetta’s lighting style, used by most of the mappers who worked on the megawad, is built around gradients; each bright swath of light is ringed by narrower gradients of the same shape, creating a soft transition down to the ambient light level. Gradient lighting had been done before—most notably in the later Chord maps and in a more rudimentary form in Eternal Doom—but its ubiquitous use in Alien Vendetta was what established it as an essential element of most types of mapping, and set the general usage style that others would follow. And whereas Eternal Doom and the Chord series used their lighting primarily from an atmospheric perspective, Alien Vendetta also places significant emphasis on lighting as a framework or a complement for other forms of detail, using it to draw attention to points of interest or create patterns that attract the eye and make scenes look more complex, which is one of the most fundamental aspects of modern lighting.

Alien Vendetta represents a synthesis between the aesthetic and artistic ideals of adventure mapping and the satisfying combat of challenge mapping

So Alien Vendetta combines aesthetics and combat to an extent that almost no PWAD had before, but more importantly, it does so in a way that’s entirely unified, so that the two halves of design enable rather than detract from each other and frequently emphasize each other’s strengths. Atmosphere can be a huge part of the feel of combat, and strong details can focus attention in the right places; at the same time, well-placed monsters can contribute to the aesthetic and the sense of adventure, and varied combat intensity can be a part of the way a mapset tells a story. And not only did the megawad establish the importance of combining the two, it also provided the rough template for how each would be used going forward into the modern era. Alien Vendetta’s basic aesthetic elements are the primitive form of most modern aesthetics; its combat was built on and revamped through Kama Sutra and the Scythe series, which essentially defined the most common styles of modern combat.

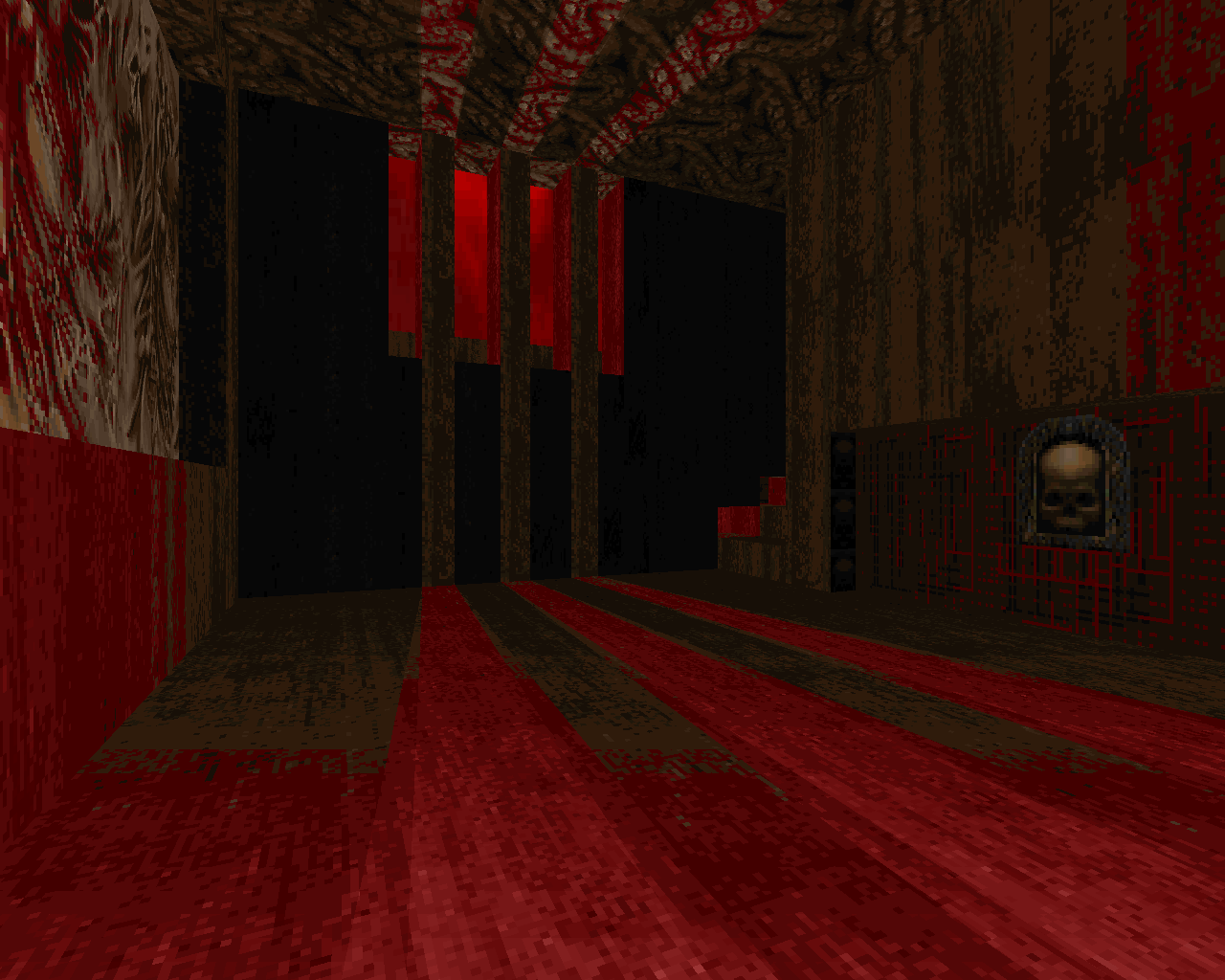

The Alien Vendetta team also gave a marked amount of attention to the “anatomy” of the megawad. While Plutonia forgoes any sense of story or connection between its maps, and Eternal Doom provides a deep feeling of overarching narrative but lacks a sense of order or pacing, Alien Vendetta balances its narrative at both the macro and micro levels—playing the distinct feel of individual maps against the broader sense of progression to make the long journey feel memorable. The map progression goes beyond Doom 2’s basic base-city-hell and builds in a stronger sense of how the player is moving from place to place. It begins with very earthy, modern tech-city settings before launching into a four-map segment set in some kind of medieval fantasy world, then throws the player back to Earth in a sequence of gleaming techbases that gradually crumble into a realm that’s equal parts Earth and Hell; after the player breaches the main gateway, the last stretch moves through a marbley, fleshy Hell and, finally, deep into a vivid crimson Hell that becomes fiery at the end. Very few maps seem randomly inserted, and the fact that the megawad is broken into a series of distinct chunks, often with logical transitions between them, helps to create the narrative. This quasi-episodic progression is given further definition—a sense of purpose, if you will—through the placement of individual standout maps. “Hillside Siege” serves as a mini-climax at the end of its episode, conveniently placed before the requisite post-map 06 story text; “Nemesis” and “Misri Halek” serve a similar role in the map 11 and 20 slots. “Sunset” (map 01) is specifically placed to establish the overarching sense of aesthetics for the megawad and stands apart thematically from the maps that follow it. “Toxic Touch” (map 10) provides a deeply atmospheric, eerily enclosed interlude to the sprawling outdoor maps of the medieval episode without departing from the theme; “Clandestine Complex” (map 24), by contrast, is a complete thematic departure, a sudden lurch into an apocalyptic earthly setting between the pure Hell episodes. Among the most thematically unusual maps in the set is “Killer Colours” (map 31), an abstract construct that shifts from one monochrome setting to another, creating mood pieces purely through color and light.

Misri Halek was the first great “That One Map” in a megawad – the one completely unforgettable map that serves as a shorthand for the entire project

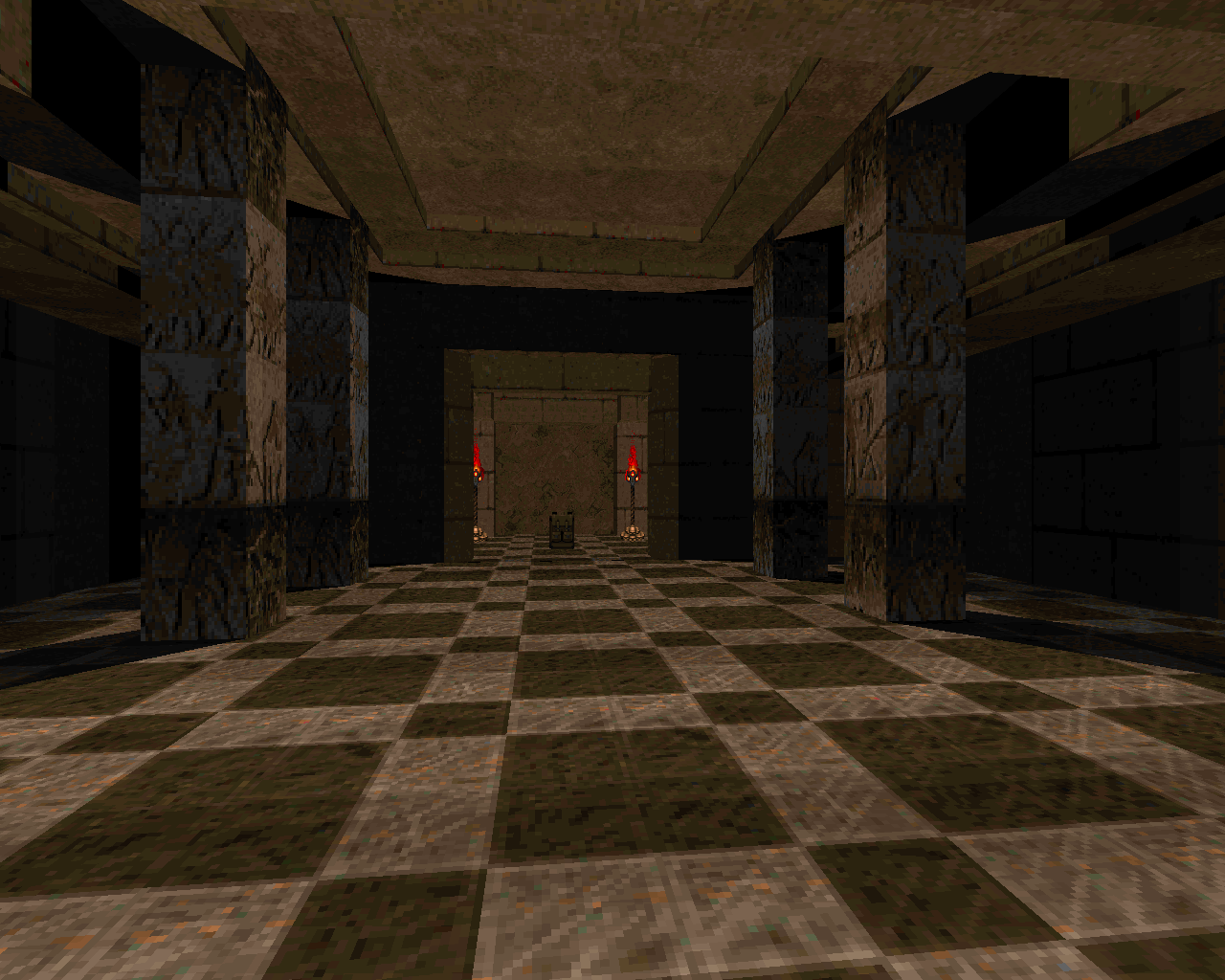

The most important map in the megawad is Kim Andre Malde’s “Misri Halek,” which is to the development of large individual “megamaps” as Alien Vendetta is to megawads as a whole. “Misri Halek” isn’t simply enormous; it offers its own self-contained journey, its own epic narrative arc. The map is like nothing else in the megawad—a mysterious, inexplicable pyramid serving as the façade for an infinite labyrinth, a forgotten enigma teetering on the edge of oblivion, crumbling into a hellish abyss like the universe being consumed by the Nothing in “The Neverending Story.” This image is as haunting as it is cinematic, and the combination of unanswered questions and shifting setting allowed Malde to build up the larger sense of adventure as the player progresses through the various sections of the pyramid. “Misri Halek” was the first great “That One Map” in a megawad—the one completely unforgettable map that serves as a shorthand for the entire project, even as the rest of the megawad remains memorable.

In a sense, Alien Vendetta didn’t do anything new and simply owes its existence to a number of WADs that came before it—Hell Revealed and Plutonia for the combat, Eternal Doom for the sense of adventure, GothicDM for the detailing—but any seasoned Doomer knows it can’t simply be reduced to its component parts. Alien Vendetta took each great thing that had been done before and did it in a more compelling way than anyone had ever done it—and then rolled it all up into a single incredible package. Doom as we know it in the modern era exists because Alien Vendetta created it. It gave us more than just a gigantic palette of mapping techniques; it gave us our entire conception of how a Doom project should be handled, the idea that Doom mapping is a complex craft for which the only proper goal is total mastery, which requires that the mapper give attention to artistry and polish in equal measure.

In many ways, Alien Vendetta was the end of an era, and I think people knew it at the time. The mappers and players of the 1990s were people for whom Doom had been a contemporary game; they got into it because it was new and exciting, and stuck with it for a little while. It was inevitable that most of those people would move on. In order to stay alive, Doom had to become a full-fledged artistic medium, a creative scene that drew in first-timers and returning nostalgia gamers alike with its endless sea of captivating creative output. I do not wish to suggest that Alien Vendetta singlehandedly enabled the survival of the Doom community—no single PWAD could have done that. But it was Alien Vendetta that opened the door, the first great release that gave Doom mapping its own distinctive modern-retro direction and elevated it into something far beyond simply a collection of add-ons for an aging game. Johnsen and company’s creation was supposed to be the last megawad before people moved on, but instead, it was the tipping point for Doom mapping to become something that lived on through a vibrant community.

-

Scythe - Erik Alm (2003)

Scythe - Erik Alm (2003)

Fast Casual Meets Fast and Furious

Scythe could perhaps be seen as a “lite” version of Alien Vendetta, but it’s primarily known for toning down other design elements and focusing on stylistic gameplay. The combat is super fast and highly steamlined, and nearly every map in the megawad is bite-sized (with a few being slightly bigger bites than others). As a result, the entire set plays like a hot knife through butter—enemies come at you so quickly and fall so quickly that you can hardly slow down even if you try, and the layouts are designed to encourage constant movement and aggressive offense over cautious defense.

Despite the relatively even speed of gameplay, the maps ramp up gradually and consistently in difficulty, with the first ones being so casual you can practically play them in your sleep and the last ones revolving around brutal shock combat that was quite daunting for the time. Because that transition is so smooth over time, it’s very intuitive to adjust to the difficulty ramp, though most new players will still hit a wall when it comes to suddenly being plunged into a massive horde battle in “Fear” (map 26) or being forced to speedrun through “Run From It” (map 28). This combination of zoomy pacing, easy-moving layouts, and steady increase in challenge makes for an overall style that could best be described as fluid, and it’s easily the most significant factor in the megawad’s long-lasting legacy.

Scythe plays like a hot knife through butter – enemies come at you so quickly and fall so quickly that you can hardly slow down even if you try

Scythe, being gameplay-focused, is quite a bit more limited in its aesthetic details than Alien Vendetta and has very few adventure elements. However, AV’s gradient lighting style is very prevalent throughout the megawad, probably because lighting is the least physical aspect of detailing and can’t possibly get in the player’s way. The later maps build up an increasingly heavy atmosphere and frequently put a strong emphasis on setting, most notably the surprising ice theme that suddenly shows up in the last couple of maps. As the first major megawad to appear in Alien Vendetta’s wake, it represents just one way to play with priorities—a way to remain firmly planted in that same all-encompassing artistic philosophy while also shifting the level design to revolve around a very specific focus. As influential as the first Scythe has been, it was the sequel that really grabbed hold of Alien Vendetta’s core ideals and laser-focused them into such a pure and engaging style that the Doom community became practically obsessed with it—but we’ll get to that later.

-

Deus Vult - Huy Pham (2004)

Deus Vult - Huy Pham (2004)

Holy Shit!

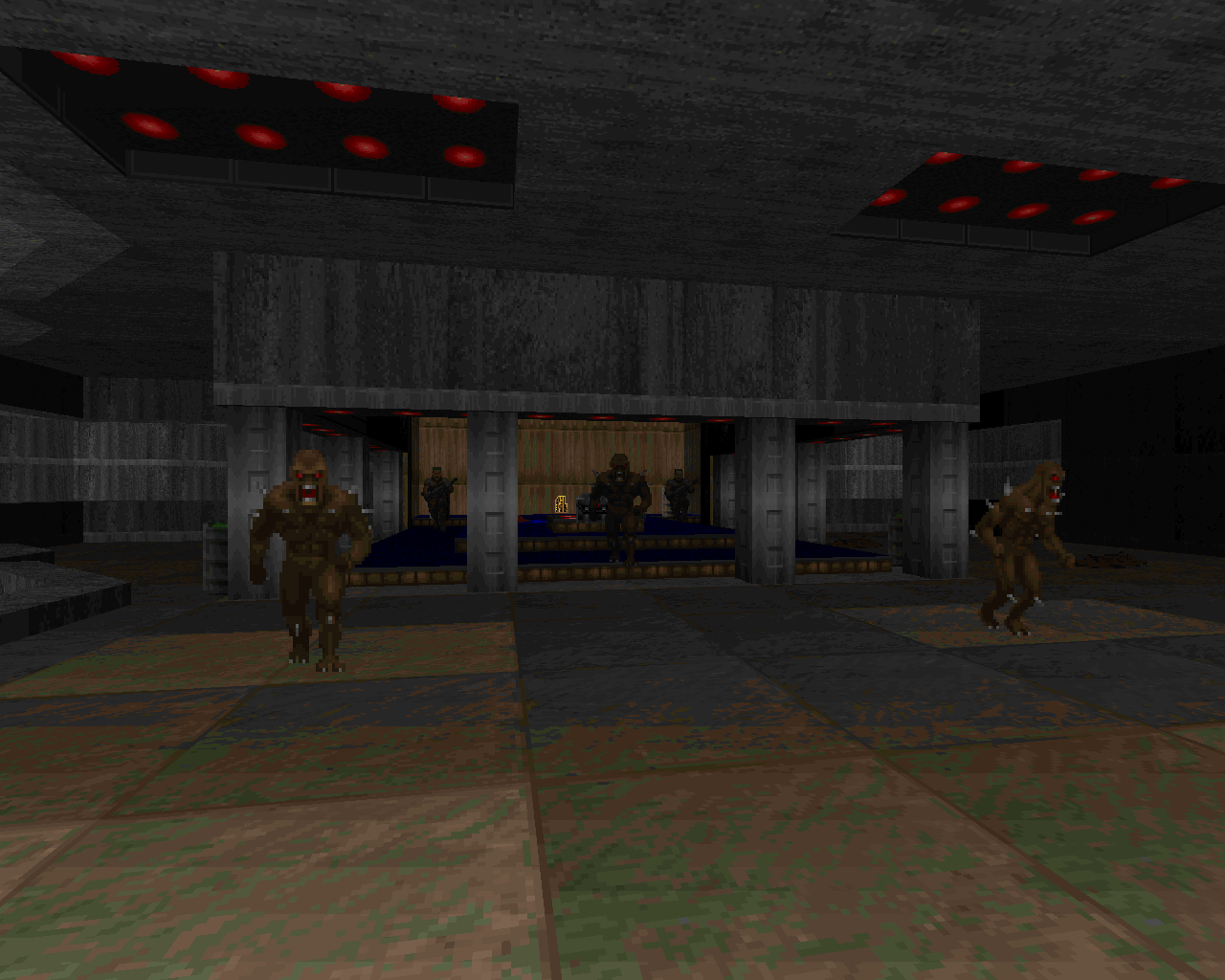

Cram all of Alien Vendetta into a single level, and you might get something a fair bit like Deus Vult, which was by far the most gigantic and ambitious single map ever created at the time of its release. Deus Vult was so vast that the release technically includes five maps—one that’s the full intended experience, and then a version that’s broken up into four separate maps just in case your computer couldn’t handle its magnificence all at once, which was highly likely. The entire incredible journey plays like the action movie sequel to “Journey to the Center of the Earth,” taking the player from a gleaming gateway laboratory down into the farthest depths of Hell, with multiple setting changes, mini-climaxes, and a great deal of cinematic ebb and flow along the way.

The map builds upon many of the detailing tropes of Alien Vendetta to create settings that are elaborate and strikingly beautiful, but it also aimed to blow players’ minds with the scale of individual areas, many of which were incomparable to anything that had been seen before. The titanic red-rock cavern and mammoth cathedral chamber in particular inspired awe on a whole new level, foreshadowing countless vistas and grand-scale combat arenas that have been created in the years since.

Deus Vult was by far the most gigantic and ambitious single map ever created at the time of its release

To keep the player under pressure within these enormous confines, Deus Vult stretches Hell Revealed-style siege combat to its limit, setting up hordes and boss monsters as a seemingly endless legion—and on top of that, it begins to work with abundant mass warp-ins of monsters, allowing arenas to appear empty and draw the player inside before suddenly becoming intensely hostile. Though most modern “slaughter” maps take a very different overall approach to their combat, DV inspired many future mappers with the sheer scale of its battles, which has become commonplace in the hardcore scene as well as in more conventional hardcore-lite maps following in the tradition of Alien Vendetta. There’s nothing quite like a map that makes a player’s brain melt while trying to take in its complexity and scope; a huge number of modern mappers have aimed to capture this feeling, and it was Deus Vult that first showed us how it could be done.