-

-

Chapter 7:

The Age of the Community Project

-

In a sense, nearly all of the great classic ‘90s megawads—Memento Mori, Icarus, Requiem, STRAIN, Eternal Doom—were community projects; it’s just that the online Doom community at the time was a very small and tight-knit band of hobbyists, with the handful of dedicated mappers forming loose confederations as needed to get the next set of maps done. Doom mappers were an odd diaspora scattered across chat systems like Compuserve, AOL, and IRC networks, as well as bulletin boards and newsgroups, communicating only as quickly and efficiently as the primordial networking technology allowed. Although there was innovation during this period, level designers had relatively simple models to follow for what made a good map, and there wasn’t such a wide gap between experienced and inexperienced mappers.

As forums increasingly became centers of activity for Doomers, the online presence grew, with more and more people engaging with the game as a social activity. This is part of how people playing Doom first began to form a group identity—having a communal space is critical for the formation of communities. With community comes a sense of shared enthusiasm, a desire to welcome and fold in new people. Thanks to forums, it also became easier for people to comment on each other’s work, and to chime in with support and excitement for new projects even without being involved in them directly. At the same time, the removal of map limits, availability of new port features and user-friendly editing tools, and broader ideas about what a Doom map could look like led to an explosion of creativity, with everyone wanting to try out new ideas.

As forums increasingly became centers of activity for Doomers, the online presence grew, with more and more people engaging with the game as a social activity

One of the lasting side effects of this enthusiasm is the community project, a group event that welcomes submissions from anyone in the forum community (though whether all submissions are accepted is up to the individual project managers). The first real community project, 10 Sectors, was held as a contest, with the top 32 submissions making up the final megawad. Three years later, the original Community Chest megawad created the model for nearly every community project that followed: put out an open call for submissions, and fill up map slots until you run out of room.

Between the source port explosion and the community project explosion, it’s no wonder the 2000s are seen as a period of wild experimentalism. With the majority of big releases coming out these new waves, it must have seemed like practically nobody was doing traditional mapping anymore. But it’s worth noting that community projects may have partly contributed to the rise of neoclassic mapping in later years. ZDoom’s advanced feature set is difficult to wrangle within the context of a big group project where the project manager has little control over contributions—particularly when you bring scripting and custom assets into the equation. Creating a community project for ZDoom invites even more inconsistency and confusion over guidelines than a regular community project, and that’s perhaps why most CPs have been limited to vanilla, limit-removing, or Boom maps. Since community projects are petri dishes for new talent, this means that the genre has encouraged a great many new mappers to work in classic formats. The controversial ZPack stood as the lone major ZDoom community project for many years, and it’s only recently that CPs have begun to encompass UDMF, the main ZDoom format, and serve as a way for mappers to learn to use that format.

Between the source port explosion and the community project explosion, it’s no wonder the 2000s are seen as a period of wild experimentalism

Another interesting side-effect of the CP ideology is the creation of national community projects. The Japanese, French, and Czech subcommunities have all launched projects for mappers within their specific countries using their own forums, collaborating in their own native languages, and leading to releases whose maps subtly reflect the culture of the parent nation. The Russian Doom community, which I mentioned earlier, is the poster child for national community projects, as the success of Sacrament led to a variety of other releases such as A.L.T. and the Whitemare series, all of which embody a very distinct national character.

I’m getting ahead of myself, though. Let’s look at where these types of projects really got off the ground.

-

Community Chest 2 - Various (2004)

Community Chest 2 - Various (2004)

One Big Mappy Family

CC2 captured people’s hearts and imaginations in a way that its predecessor didn’t quite manage, though CC1 carried the seeds for many of the same ideas. And whether you break it down into individual maps or view it as a larger flow from beginning to end, it’s fairly easy to see why. CC1 has a lot of voices, but it’s fundamentally a set of basic Doom maps, representing common conventions of the era; only the relatively new mapper Magikal approached the project with a particularly grand and unique ambition, and his “Citadel at the Edge of Eternity” (map 29) drew extremely mixed reactions even at the time. The end result was something like a ‘90s team megawad with less quality control or experience behind it. Mappers weren’t approaching it as a way to showcase their best work, to outdo each other, to stun the audience with how unique and impressive their ideas could be.

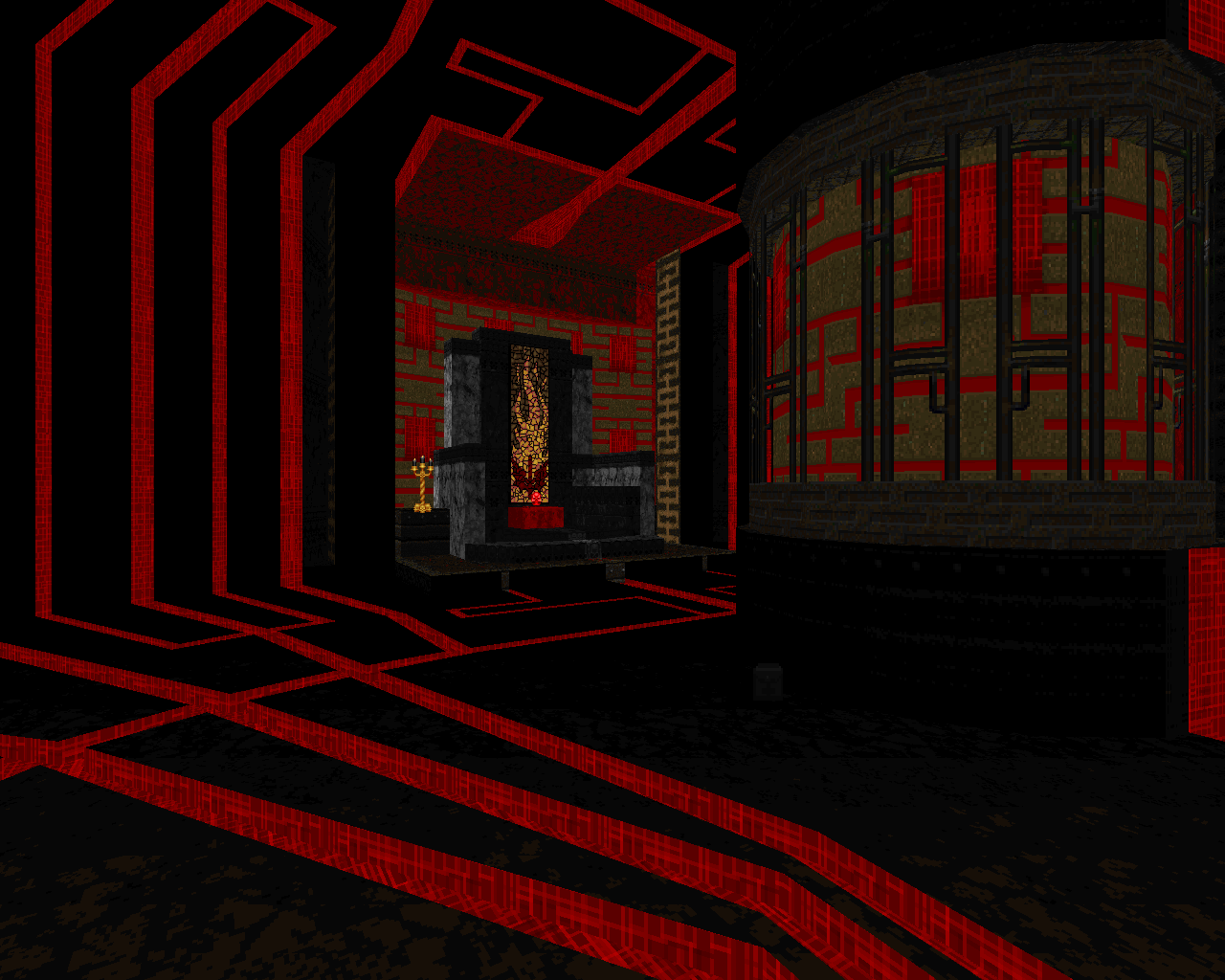

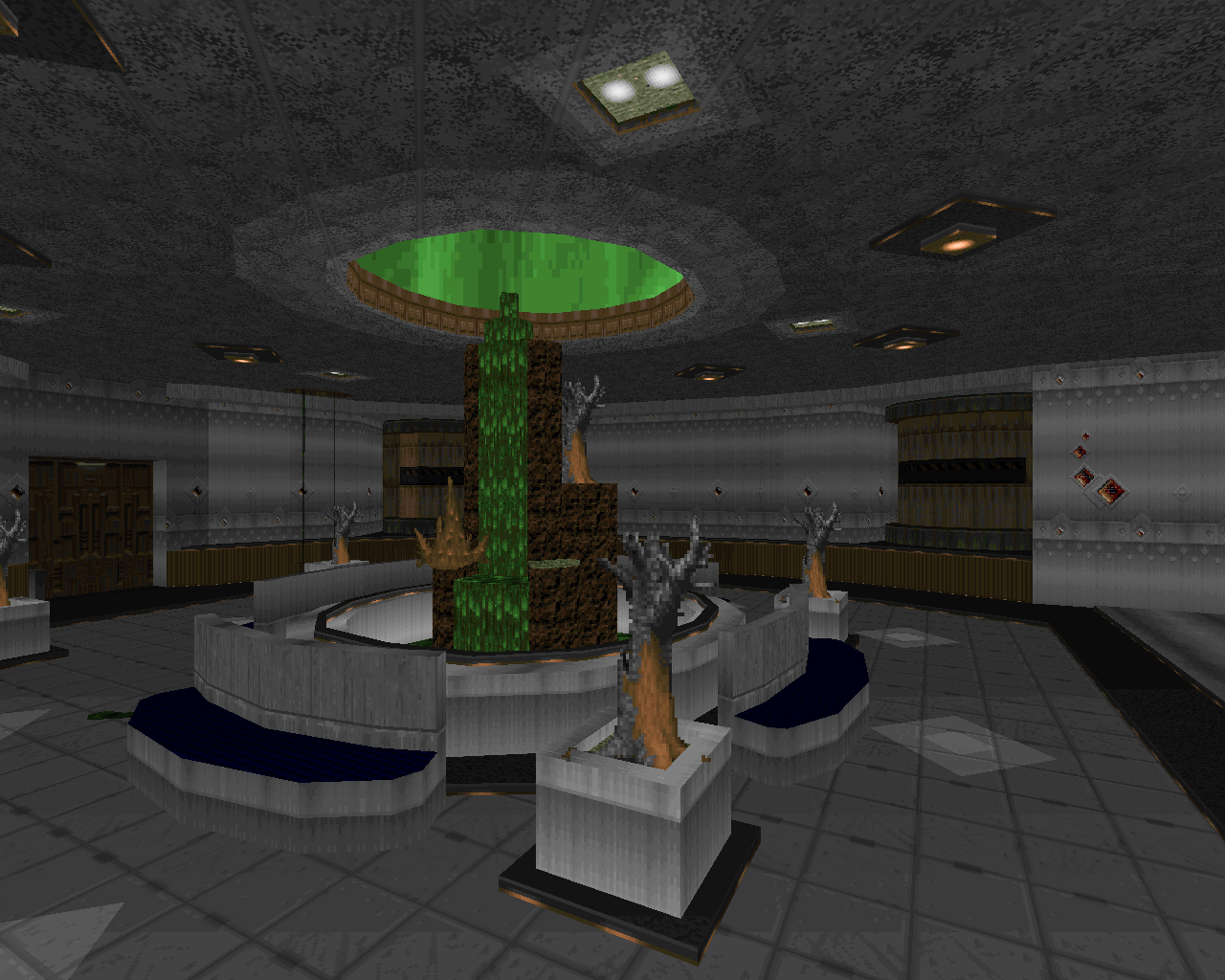

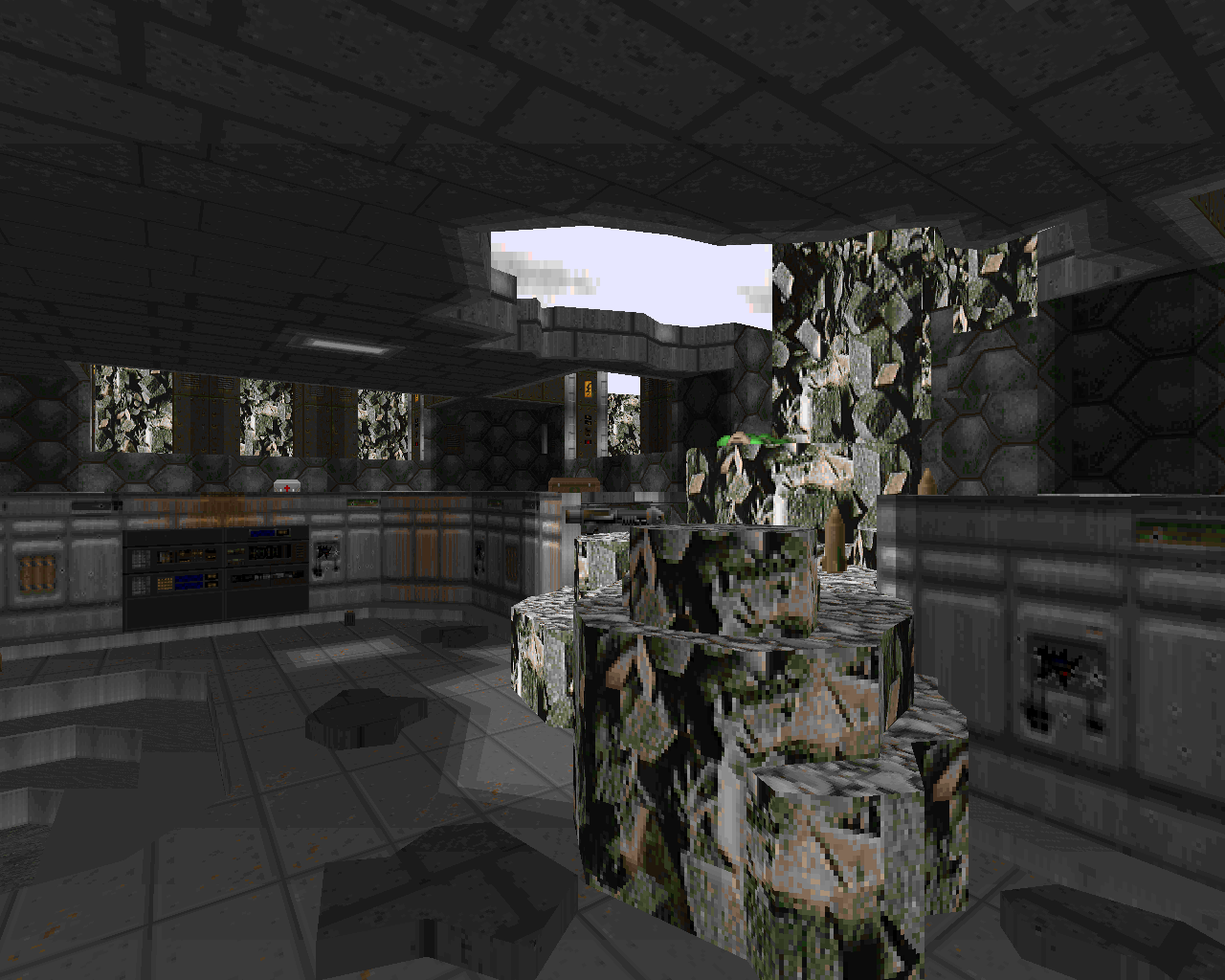

CC1 must have sparked something, though, because CC2 followed a little over a year later, and I believe the wild fervor with which many of its mappers approached their contributions was the flame that ignited the whole community project genre, which has produced dozens of releases (and many vaporware projects) to this day. A list of the megawad’s many standout maps gives some sense of just how diverse they are: Iori’s flowy, Knee-Deep in the Dead-themed “Coolant Platform” (map 02); The Flange Peddler’s highly modern, detail-laden “Slige Control” (map 03) and “To Hell and Back” (map 07); Lutrov71’s “The View” (map 06), a wide-open epic with denser combat and many sweeping vistas; The Ultimate Doomer’s gonzo sandbox adventure “City Heat” (map 15), with its perpetual-motion river and numbered objectives; Andy Leaver’s sinister, Alien Vendetta-esque “Through the Black” (map 17); Kaiser’s huge, complex dungeon crawl “Internal Reaches 3” (map 18); Hirogen2’s “The Marbelous Three,” an archeological dig site that blends heavy atmosphere and doomcute sector detailing; The Flange Peddler’s lovely Limbo homage, “Enigma” (map 20); Cyber-Menace’s “Death Mountain,” which remakes a locale from A Link to the Past, complete with cavern shortcuts and one hundred thousand sector stalagmites; Dr. Zin’s incredibly creepy haunted space station, “Geist Halls” (map 26); Use 3D’s “Gethsemane” (map 27) and Linguica’s “No Room” (map 28), a pair of massive hell maps with plenty of memorable scenes; Boris’s narrative-driven “Event Horizon” (map 29), with its advanced Boom features and sector art monster invader; and Chopkinsca’s “Sodding Death” (map 32), a glorious adventure map with an intricate temple crawl at its heart. Even some of the weaker maps are joyfully concept-driven, such as RjY’s “Elixir” (map 05), which is stuffed to the gills with popcorn zombie hordes.

There’s something about having all those wildly different maps together that makes each one more exciting to play, like going through a box of chocolates

Padding out a paragraph with a long list of individual maps isn’t something I take lightly; but the fact is, a great community project is defined by its individual maps. If you’re talking about a conventional megawad created by one or two people, or even a medium-sized hand-picked team, you’re going to look at overarching project goals, the basic stuff that binds the whole set together; you probably wouldn’t mention more than a few of the best maps as examples, and typically those best maps are simply the best at doing the same things that define the rest of the megawad. But while most megawads are about the whole, a community project is really about the sum of its parts. There’s something about having all those wildly different maps together in a more or less random sequence that makes each one more exciting to play, like going through a box of chocolates. Sure, you’ll get a coconut or one of those weird chewy things every now and then, and there will be some basic nut clusters and whatnot, but it’s worth it for the raspberry cremes and salted caramels—or, depending on your tastes, perhaps the other way around—and because you never really know what you’re biting into, there’s a certain thrill that you can never truly get from a single-author or small-team mapset. The variety itself lends weight and vitality to the project, creating a sort of emergent property that makes each community mapset distinct and memorable—though of course you need to have a lot of good maps in the lineup for it to be the right kind of memorable.

Towering over every other map in CC2 is B.P.R.D.’s legendary “The Mucus Flow” (map 24), which is almost certainly the first map anyone thinks of when they think of the megawad. Following in the footsteps of “Misri Halek,” it was the second great “That One Map” in a megawad, and it both entrenched the idea that every large project should have at least one completely unique standout megamap and helped to shape what future megamaps would look like, particularly the impression that many of them would seek to leave behind. In the midst of everything else in CC2, “The Mucus Flow” is completely alien, surreally beautiful, hinting at worlds beyond worlds but only giving you the tip of the iceberg, as though Doomguy’s ten thousand adventures in Hell are just part of a broader multiverse and suddenly you’ve gotten the merest glimpse of something akin to heaven. The ethereal music, towering structures, and enigmatic custom textures all contribute to this feeling. But on top of that, it’s also a very conceptual map; ammo and health only exist in a few large caches throughout the map, one of which requires running an infinitely respawning chaingunner gantlet to return to and the rest of which require keys, forcing you to think hard about how, and whether, you’ll tackle the whole thing or if it’s better to simply make a break for the exit. All of this makes it virtually impossible to talk about CC2 without looking at the impact that “The Mucus Flow” has on the experience of playing every other map in the megawad, and conversely, the way that the presence of all the other maps allows “The Mucus Flow” to stand even taller.

Since Community Chest 2, every major community project has had mappers vying to create That One Map

Since CC2, every major community project has had multiple mappers vying to create That One Map; RottKing’s “Black Rain” from CC3 (map 12) is one of the more notable and successful examples. But when it comes to community projects, everything can be a double-edged sword. CC4 is so full of magnum opuses that it becomes a source of fatigue, and it’s easy for players to start wishing for some shorter and simpler maps to lend more meaning to the big, awe-inspiring ones—although lupinx-Kassman’s “Interstellar Sickness” and “Shaman’s Device” (maps 20 and 21) still manage to be That One Map in spite of it all.

It goes without saying that the other potential problem of community projects is that they’ll always have weaker maps in them, even the projects that value quality control. It’s simply a consequence of allowing anyone to contribute, the tradeoff that every community project makes for the added value that its inclusivity offers to the broader community. CC2 itself certainly has its share of maps that are perceived as weak, and when it was released, it was accused of adding in a lot of filler to pad itself out to megawad length. In recent years, large invite-only group projects like Back to Saturn X appear to have signaled the gradual dying-out of truly high-profile community projects, simply because they are an easier way to ensure high quality. In this day and age, community projects tend to be more of a way for newer mappers to grow and showcase what they’re capable of, which carries on the genre’s legacy of welcoming people into the community. But in my opinion, that volatile blend of contrasting mapping styles and sensibilities, along with the inevitable handful of even more unique maps that stand out above the rest, is something that can’t be replicated by any other means, and the rare exceptional community project remains something special.

-

Congestion 1024 - Various (2005)

Congestion 1024 - Various (2005)

Thinking Inside the Box

Within the field of community projects, there’s a popular subgenre of projects that are built around seemingly restrictive limitations. 10 Sectors was the first mapset of this type, but Congestion 1024, which required mappers to build the playable space of their maps within a square of 1024 by 1024 map units (which is super tiny, for those of you who may not know what a map unit is), was the megawad that popularized limitations. This community megawad was followed by wave after wave of projects with similar restrictions, not only community projects but also solo mapsets like Dutch Devil’s Zero Tolerance (which also uses the 1024 by 1024 limitation).

The idea behind these projects, and the reason they’ve been so successful, is that their limitations are designed to require clever thinking, which sparks creativity and often leads to surprising results. They also create a unifying theme, something to tie the whole project together, even as each of the many mappers involved tackles the problem in a completely different way, with a different stylistic approach.

Their limitations are designed to require clever thinking, which sparks creativity and often leads to surprising results

Congestion 1024 and its direct spiritual successors were particularly compelling in that their restriction inherently ensured that every map was bite-sized and easy to digest, with the whole megawad being extremely quick and breezy to play through. Limitation projects have never been limited exclusively to size restrictions, though—their restrictions over the years have covered everything from texture and monster usage to the size of editor grid that mappers are allowed to use.