-

-

Chapter 8:

The Second Coming

-

With all of this experimentation in the early to mid-2000s, it’s no wonder the community felt a little…unmoored. On the one hand, you had the growth of source ports turning Doom into a completely new game, and on the other you had free-for-all community projects with bizarre ideas and an arguably greater emphasis on enthusiasm than consistency or quality. An unspoken question loomed over everything: what was even Doom anymore? The mapping community’s heavyweights had created Alien Vendetta to lay a treasured memory to rest as they moved on to other games, an epitaph marking the pinnacle of what seemed possible to accomplish with their favorite aging engine; who were all these upstart mappers crawling out of the woodwork and carrying on the tradition in weird new ways?

You’ll hear many people say that Scythe 2 was a rebirth of classic gameplay, a renewal of commitment to the ideals of the community’s early mappers and players at a time when people feared those ideals were fading out of existence. And to some extent, that’s true—especially the part about the fears. The community has seen many warring ideologies, many trends that came and went and came back, and people are always worried that the things they love will be forgotten.

Many feel that Scythe 2 was a rebirth of classic gameplay, a renewal of commitment to early ideals at a time when people feared those ideals were fading out of existence

But consider that Scythe 2 came out in 2005, just three years after Alien Vendetta—and even that small gap was bridged by the first Scythe as well as Vrack 3 in 2003, Deus Vult in 2004, and Kama Sutra earlier in 2005. Mapping never died; it never had to be resurrected. Erik Alm’s magnum opus was simply the next natural step in the evolution of the megawad. For that matter, Scythe 2 wasn’t much of a throwback, and it certainly wasn’t nostalgic. The intensity of the large-scale combat, the beauty it achieves through mass detailing, the format in which it’s presented—none of that has any real analog in the 1990s. It’s drawing directly from Alien Vendetta and its other successors. It felt incredibly modern at the time, and that was exactly why everyone adored it.

-

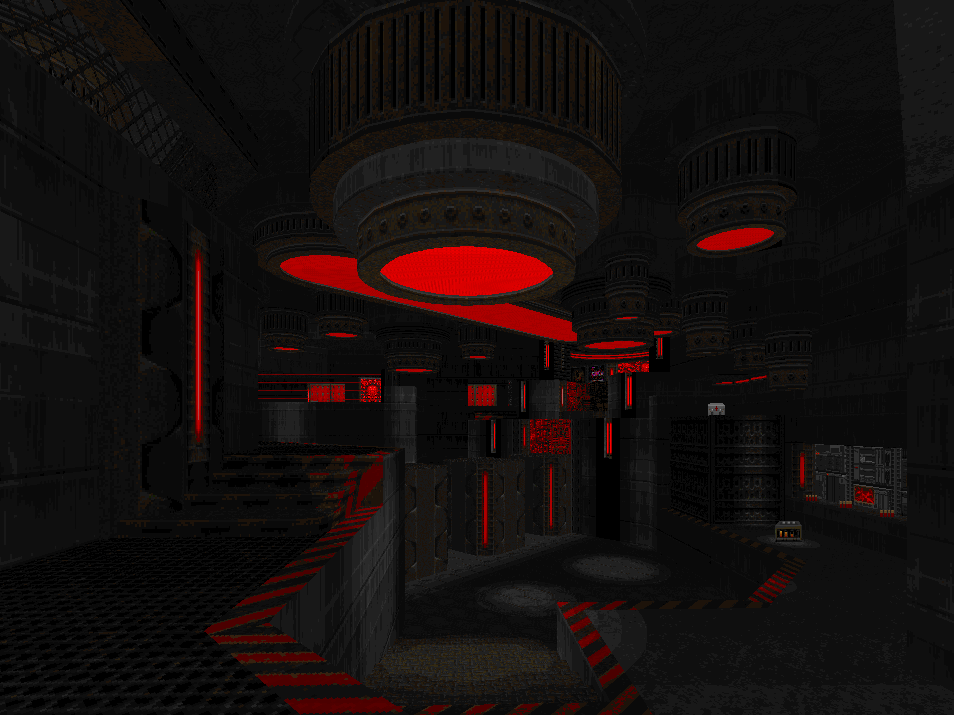

Scythe 2 - Erik Alm (2005)

Scythe 2 - Erik Alm (2005)

The Very Model of a Modern Major Megawad

That said, Scythe 2’s ripple effect on later mappers is truly immense, and it’s hard to disagree with @dew's claim that it is probably the second most influential PWAD of all time after Alien Vendetta. Never mind the host of direct imitators; Scythe 2 hit on a certain something, a magic formula, that modern mappers tend to draw on regardless of what mapping school they’re in or who they credit as their most direct influences. Simply put, this megawad defined what a modern mapset looks and feels like; it tapped into the bloodstream of the Doom community and fed us a drug. It’s only in the last few years that people have really begun to challenge the idea that good mapping is synonymous with Erik Alm’s mapping principles, but those principles remain extremely influential nonetheless—probably because Alm’s maps were so damn good.

Alm’s most significant contribution to Doomdom was his sense of pacing—both the pacing of individual maps and the pacing across a larger mapset. The driving principle of a typical Alm map is that it never stops moving—there’s always something to do, something to try to pick up, something you need to kill or escape from, and you can always see pretty clearly with some quick observation where you need to go next to avoid any lull in the action. “Conveyance” is a term I’ve heard used to describe this—it’s the idea that the map design is conveying you to wherever you need to be, whether it’s through visual clarity or the direction of the combat or items placed in your path. Of course, the mapper can use conveyance as a weapon against the player by drawing them into a trap, but it’s usually more about the positive reward of having the map be a nonstop, well-choreographed experience. The other key element of Alm’s pacing is a sense of variety, which is usually created by moving back and forth smoothly between incidental combat—the quick random combat that you engage in while moving between major points in the level—and setpiece combat—the larger choreographed fights that happen at major points in the progression or in specially designed arenas. The sense of constantly rising and falling action keeps the player engaged over the course of the map, demanding constant attention and providing consistent gratification.

Scythe 2’s ripple effect on later mappers is truly immense, and it is probably the second most influential PWAD of all time after Alien Vendetta

The overall pacing of the megawad is handled in a similar fashion. Whereas Scythe 1 provides a steady ramp-up from very quick, simple maps to challenging, monster-dense ones over the course of the entire megawad (which was itself a pretty strong way of hooking the player’s interest), Scythe 2 refines the formula quite a bit through the use of shorter five-map episodes, each with its own difficulty ramp. Map 01 is easy, and then the maps gradually become harder through map 05, the final map of the first episode; then you start the first map of the next episode, which is a drop down in difficulty from the end of the previous episode, but an increase in difficulty from the earlier maps of that episode; difficulty ramps up again, and the end of episode 2 is harder than the end of episode 1; and so on. In this way, Alm was able to create the sense of rising and falling action over the course of the megawad and keep the pacing varied, while still gradually increasing the challenge from beginning to end. A key tool in creating this sense of pacing is the then-controversial death exits, which force a pistol start at the beginning of each episode, allowing for more precise control of each individual difficulty curve—a trope that many of Alm’s successors have copied directly. Even if they’re not working in an episodic format, post-Alm mappers tend to recognize the need to vary a mapset’s pacing through mini-climaxes, breather maps, and surprise concept maps (an idea that Alm also helped to pioneer in Scythe 2 by inserting maps like the single-monster horror scene “Mr. X” (map 16) and the pistol/rocket launcher/chainsaw-only “Doom Gardens” (map 21) into his lineup).

Similar to Alien Vendetta, Scythe 2 aims for a strong blend of combat and aesthetics, but it offers improvements in both areas. Rather than just falling back on the siege warfare of Hell Revealed and Alien Vendetta, where the player pushes forward through entrenched opposition and the greatest danger comes from being flooded by large mobs, Alm mixes it up with a primary combat mode that’s more fluid or dynamic, with a lot of attention to creating multiple angles of pressure so that the player isn’t truly safe anywhere and either can’t retreat to a point of safety or isn’t particularly advantaged by attempting to do so. It uses conveyance to draw you into dangerous situations, but it also lets you behave aggressively in response, giving you room to maneuver, a chance to prioritize targets from among a highly mixed array of enemies, and above all a way to deal with threats relatively quickly. The player’s firepower is commensurate with threat level—the more you’re facing, the more ammo and better weapons you have, which helps to avoid grind.

Almost every major megawad since Scythe 2 has drawn heavily from the tropes used by Scythe 2

In a similar way, the maps in Scythe 2 are more aesthetically detailed than Alien Vendetta, but also cleaner. Building on AV’s aesthetic, Alm keeps the playable space functionally clear while focusing the detail on the walls, ceilings, and areas the player can’t reach, which also has the effect of placing the detail at an easily viewable distance, concentrated on areas that draw the player’s eye. Alm enhances his relatively moderate line count with specific detail tropes such as roof cornices around the upper edges of buildings, ceilings composed of patterns of metal bars, jagged walls, stacks of gently curved rock structures with liquid falls, and arrays of draping vines, all of which have become foundational elements of modern detailing. It would be a bit silly to say that Alm invented all of these visual elements—indeed, many of them are borrowed and heavily refined from Alien Vendetta and Eternal Doom—but he certainly brought them together into a distinctive, definitive look. Even the idea that an individual map maintains consistency by being constructed entirely from permutations on a single visual theme, with a handful of textures used throughout, is most easily traceable back to Scythe 2’s episodes.

Whether it’s episodic or traditionally linear, stock or custom textured, with custom monsters or without, almost every major megawad since Scythe 2 has drawn heavily from the tropes that Scythe 2 used. Even Eviternity, which as of this writing is the latest blockbuster megawad, fits Alm’s model to a tee—five-map episodes with death exits, a stepped difficulty curve, combat that’s driven as much by speed as challenge, a few new monsters to keep things interesting. The Scythe 2 formula certainly isn’t the only way to make great maps, but it’s so oft-repeated because it hit the sweet spot that seems to make the most people happy: simple but not too simplistic, hard but not too hard, varied but controlled, beautiful but not distracting or confusing. It’s the middle ground that most people can agree on, which is why a PWAD rarely manages to approach the popularity of Scythe 2 without beating it at its own game.

-

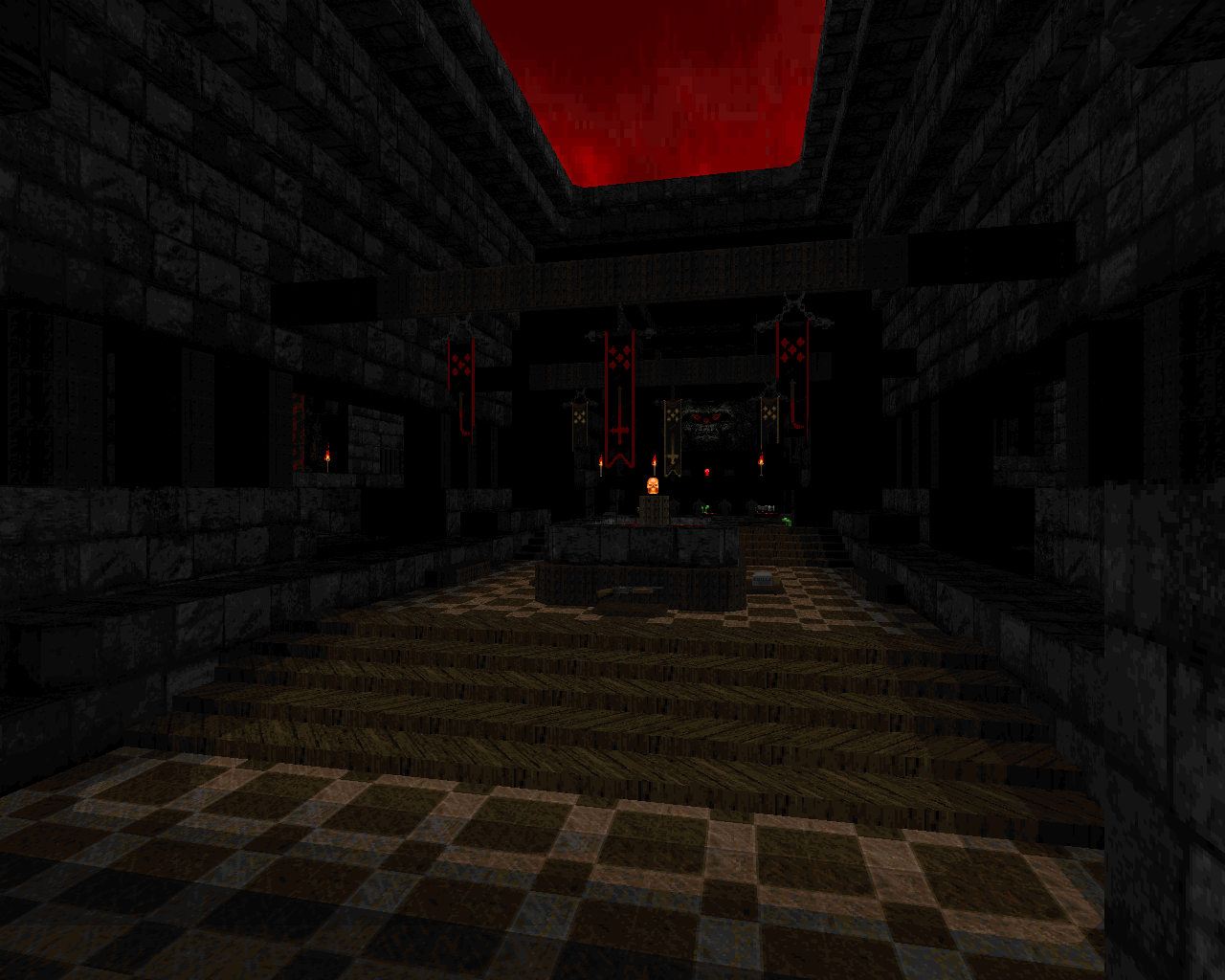

Plutonia 2 - Various (2008)

Plutonia 2 - Various (2008)

The Tipping Point

Though its visual style, certain elements of monster placement, and a handful of homage maps are reminiscent of the original Plutonia, this sequel is notorious for having gameplay and atmosphere that bear little resemblance to its namesake. After years of troubled development, Plutonia 2 saw a change in leadership, and its new manager, Vincent Catalaa, masterminded an influx of passionate new mappers along with contemporary heavy-hitters like Gusta, Thomas van der Velden, and Eternal.

As a result, the project received a major “overhaul” that resulted in its map lineup being almost entirely gutted and replaced, mostly in the name of improving gameplay; despite the enormous amount of work involved, this ironically helped to finally get it across the finish line. The result mainly takes its cues from the hard-hitting megawads of the mid-2000s, including Alm’s style of design; in particular, Gusta’s many contributions to Plutonia 2 draw from and expand upon the lessons that he learned while creating Kama Sutra.

The release of Plutonia 2 was the major tipping point for the era of Scythe-inspired mapping

The release of Plutonia 2 was the major tipping point for the era of Scythe-inspired mapping. The following year saw the release of the high-speed darkwave0000/Joshy tag-team megawad Speed of Doom, and from there came the cascade of combat-driven limit-removing and Boom mapsets that dominated much of the 2010s.

-

Valiant - Skillsaw (2015)

Valiant - Skillsaw (2015)

Up to Eleven

If there’s any one person who brought Scythe-style design to the next level, someone who is even more Alm than Alm himself, it’s skillsaw. 2011’s Vanguard and Lunatic saw refinements on the episodic formula and streamlined combat of Scythe 2, but it was Valiant that seemed to reach the highest heights of what a modern Boom megawad could achieve.

Skillsaw took everything that was stylistically great about Scythe 2 and dialed it up to eleven, while also making it even more fun and accessible for the typical Doom player. The episodes are still there, but they’re more flexible; the number of maps in each episode varies as needed to accommodate skillsaw’s flair for in-map storytelling, and there’s a lot more variety within each episode theme—for instance, the way the hell episode shifts from hot, rocky hell to cyberflesh hell to fragmented void hell to a gothic fortress that integrates elements of all of the previous subthemes—which makes the whole megawad feel constantly fresh throughout its significant length.

Valiant seemed to reach the highest heights of what a modern Boom megawad could achieve

Skillsaw is also a master of using concept maps and varied mechanics to keep the gameplay fresh, as seen in the infamous escort mission of “The Mancubian Candidate” (map 07), the suspense of “14 Angrier Archviles” (map 09), the barrel-themed “Implosion” (map 14), the extremely impolite welcome from the suicide bombers in “Screams Aren’t a Crime…Yet” (map 15), and the climactic boss fight of “Electric Nightmare” (map 30), among others. Skillsaw’s maps tend to be more nonlinear than Alm’s, while still keeping (and improving upon) the strong sense of conveyance and clarity, which provides a more variable experience while still allowing the mapper to maintain sufficient control over what happens. On top of all that, you have even more beautiful texture themes and settings, even smoother interplay between incidental and setpiece combat, and custom weapons and monsters that fit more smoothly with the stock resources. Add it all up, and you have a megawad that’s immensely satisfying for a huge range of players, perhaps the closest anyone has gotten to universal appeal.