-

-

Conclusion

-

The whole history of Doom mapping is wonderfully complex and varied, and there’s no way to truly sum it up in a few simple statements. But at the same time, studying the history and writing this article helped me appreciate the long-term narrative in ways I never had before. When I stepped back and looked at everything in chronological order, I saw the same narrative arc repeating twice, forming two halves of the Doom community’s history, one beginning almost exactly where the other ended. In the beginning, you had experimentation with priorities, people trying to understand combat and aesthetics separately, until Alien Vendetta came along and wrapped it all up in a neat little bow. Then, just as people thought their work was done and Alien Vendetta appeared to be set in stone as the last great classic megawad, people started showing up and creating all sorts of oddball experiments, from maps crammed with advanced port features to community projects where there were no rules or parents and anything was fair game. Dismayed by this seemingly endless party time, many mappers sought to return to the classics and create maps defined by traditional ideologies, presenting their neo-old-school styles with a level of polish that had never been seen before. And now here we are, watching a new generation of mappers grow up as they find ways to combine the best of everything that’s come before into a single mapping movement—one that seems to be centered on GZDoom, which so many people once considered antithetical to great mapping. The story of Doom is the story of division and synthesis.

A.L.T. (2012)

This article is definitely not the whole picture. It has been a very broad overview of what I consider to be the main schools of Doom mapping so far, as exemplified by the creations that inspired or revitalized them. It goes without saying that there’s a lot I wasn’t able to cover here. There are the great classic Doom clone megawads of the 1990s, like Memento Mori and Requiem, and there’s the cozy 2000s classic-with-tons-of-detail style of folks like Paul Corfiatis and Dutch Devil. There’s the timeless trend of faux-realistic sector furniture and objects, or “Doomcute,” which began with Evilution, was epitomized by the likes of TVR! and Kama Sutra, and lives on to this day. I haven’t even begun to talk about joke maps, the entire history of multiplayer mapping, or the extremely prolific gameplay modding scene that GZDoom has enabled.

The same narrative arc repeats twice, forming two halves of the Doom community’s history, one beginning almost exactly where the other ended

There’s nothing new under the sun, and as I’ve alluded to a few times in this article, a lot of people’s inspiration comes from outside of Doom—from other video games, other media, or the grand circus of Real Life. I certainly don’t mean to suggest that concepts like conveyance, mood lighting, and the uncanny were invented by Doom mappers; clearly that’s not true. But it took innovative people to take those concepts and give them a context within Doom as an art medium, to use them in a way that is uniquely Doom. This article has been about those people.

Nor do I wish to imply that the evolution of mapping trends has simply been a series of straight lines. The family tree of mapping influence is more like a spiderweb. Take Speed of Doom: it was created by two mappers, one of whom built super-fast but tough maps in the vein of late-game Scythe 1, and the other of whom combined the style of Scythe 2 with the mood and aesthetic of death-destiny’s Disturbia. Disturbia itself was basically Hell Revealed meets The Mucus Flows, while Scythe 2 combined Alien Vendetta with the amped-up feel of side-scrolling action games and the smooth flow of Knee-Deep in the Dead, perhaps. Nobody has just one source of inspiration, and it’s rarely a mapper’s conscious decisions that define their mapping style—it’s the unconscious ones. It’s only by looking at overarching trends that you can get a real sense of where all the ideas are coming from. But that also doesn’t diminish the value of individual creative voices, and there’s no telling what sorts of cool combinations we’ll see in the future.

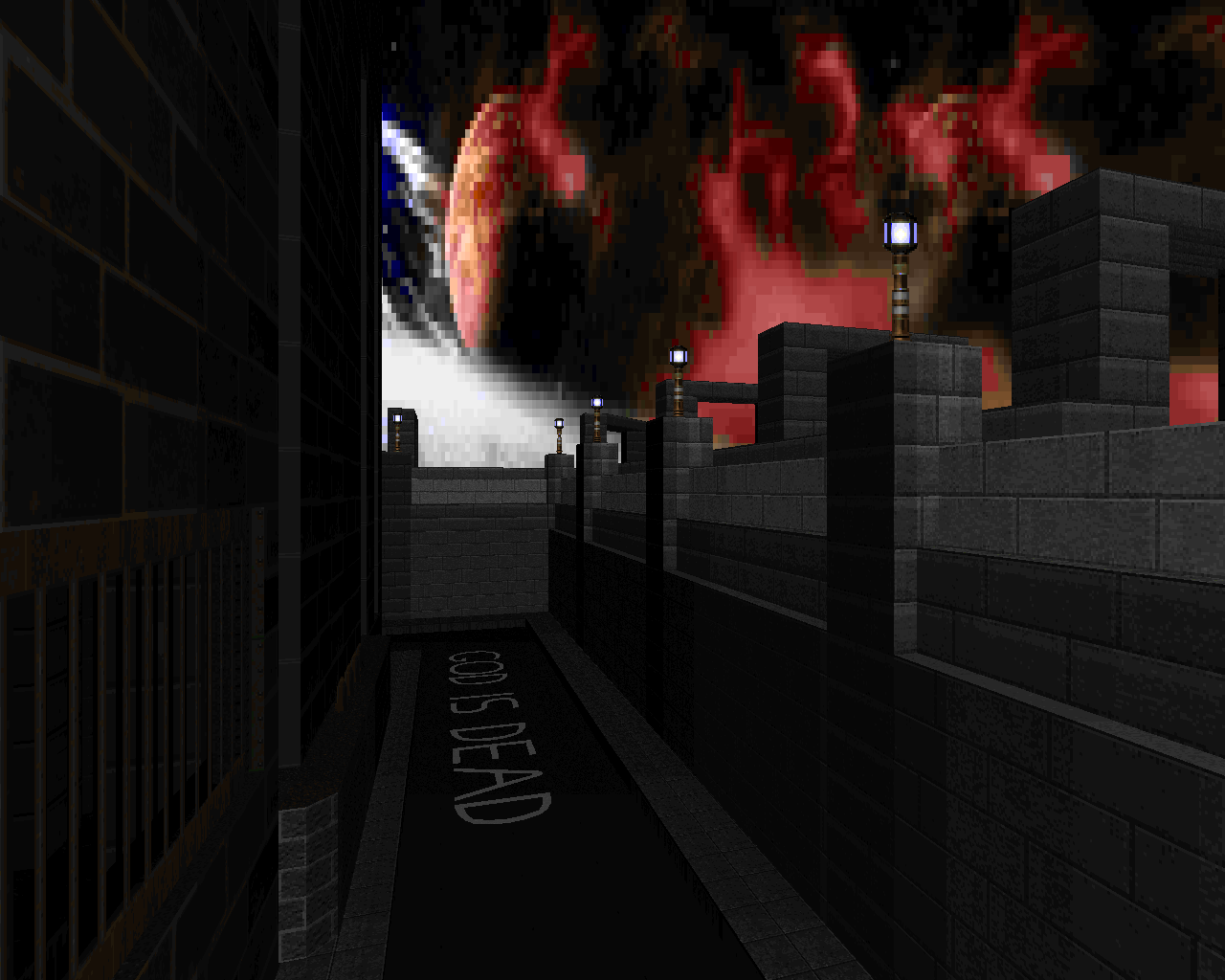

Lilith.pk3 (2017)

Caveats and disclaimers aside, the coolest thing about writing this article has been the realization that change is inevitable, and it’s what keeps the mapping community alive. Doom is already in the middle of moving on to great new things. Even just a few years ago in the mid-2010s, when we were getting incredible releases like Valiant and Sunlust delivered to us on a silver platter, it was hard to see how things could get any better than they already were. I think a lot of us at the time were worried that Doom had reached a plateau and might start to stagnate. But here we are, as overwhelmed by the awesomeness of new releases as we’ve ever been—and it’s not because we kept trying to fine-tune what we were already doing, but because we found a way to strike off in a new direction. Or maybe, in reality, it’s a bit of both.

Total Chaos (2018)

So the old question remains: what is even Doom anymore? Fellow Doomers, I believe it is whatever you want it to be. You’ll never find another game that offers a single person the artistic flexibility or the decades of accumulated design knowledge that this one does—and you can still bring something unique to the table. Go forth and create!

(with huge thanks to @Demon of the Well, @rd., @Linguica, and @dew for input and feedback)