-

Ultimate Doom, limit-removing, 9 maps

By a comfortable margin, SIGIL was the most anticipated, previewed, played, pored over, replayed, analyzed, praised, and shat on release of the year. That was inevitable. Romero is Romero. Ultimately, however, we intend to judge work on its own merit. This special mention is a compromise between that goal and the undeniability of Romero's star: no, it is not getting an "11th Cacoward," but now that it is a runner-up, we will discuss it at greater length. The maps, that is. If curious about the Beast Box, the collection of cool art, music, and memorabilia bundled with its physical shipment, you can learn more on any of several dozen online gaming publications.

To understand SIGIL in the greater context of Romero's work, one must hop a teleporter back to the beginning. In 1993, with the engine in flux and John Carmack a mere shove of a swivel chair away, new functionality could be coded in as Romero saw fit. Accordingly, many memorable rooms in Knee Deep in the Dead are conceptual one-offs, showcasing a core action or effect: Toxin Refinery's blackout ambush, and its endlessly intricate secret chains; Phobos Lab's chilling strobe-lit ending; Computer Station's jumps off rising stacks. The opener, Hangar, was famously crafted as an object lesson for the new player in the Doom engine's features and its improvements over Wolf3D.

By the time of the expansions, the pool of actions had been iced over, and besides, showing it off bare had lost its novelty. Romero began more often to pair existing mechanics with visual motifs of his making, assembling features the player could interact with and understand at a glance. The story of Perfect Hatred is the revisitation and unfolding of its central complex. The Living End's vast depths are home to twisted bridges that rise dramatically into place; the northern wing has the player repeatedly hit lavabound switches to raise narrow walkpaths; the east wing is defined by its mangled trident of bridges, a switch at each spear. Gotcha!'s wacky gimmickry is nothing if not a raw distillation of this approach, one that SIGIL would latch onto and foreground yet further.

SIGIL's evil eyes and Baphomet exits are the most overt such ideas, but hardly the only ones. A taste of the rest: M2's decay leads walls repeatedly to disintegrate. M5 is powered by occult kinetics—lifts, rising bridges, and rooms that shuffle and reorder like phantasmal Rubik's cubes. M9 is laced with needle crushers wielded to crucify rather than flatten. Throughout the episode, distinct zones of space are defined by distinctive gameplay concepts, never more obvious than in M4's three-headed trial of nimbleness and nerves. The wealth of ideas underlying every moment of SIGIL's runtime—from the combat, to the progression, to the scenery—is its greatest strength. There is little fluff. Romero knew what he wanted from each stage, and that confident vision is projected crisply into life. Tight movement is SIGIL's keystone, and the numerous overseer cyberdemons make blood-stirring adversaries.

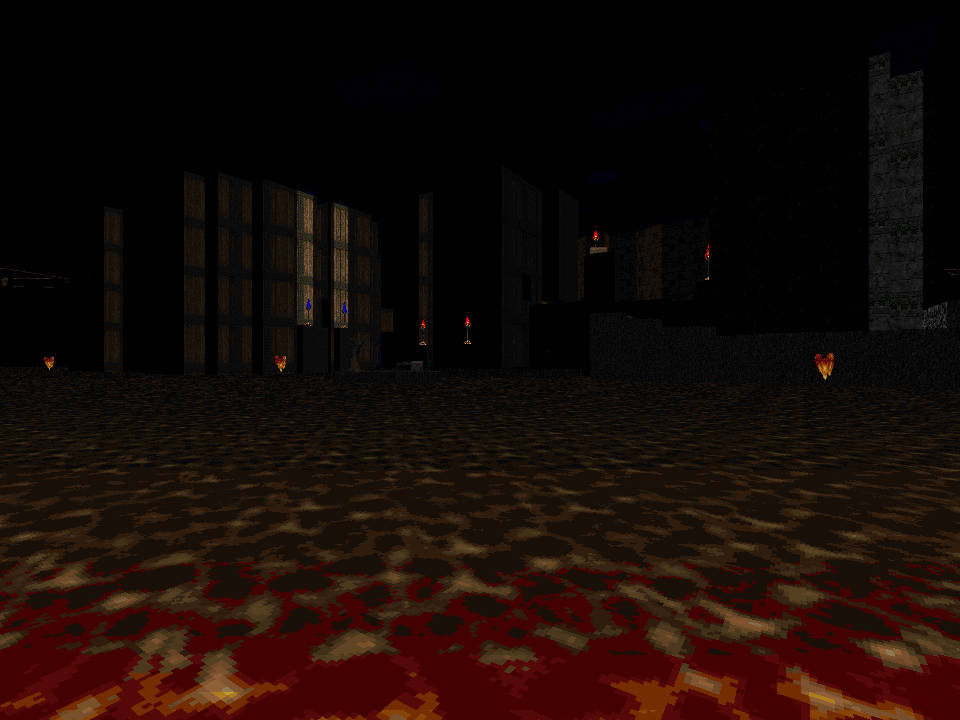

The mood is primed by a bold choice of Buckethead music or, even better, smart MIDI selections from @Jimmy's catalog; and the atmosphere is thick, with marble and wood, flesh and decay, gloom and void, lava and hell fissure, all called forth for an enigmatic, memorable take on hell. You can look into the darkness and feel disembodied, that the surface is impossibly far. That the cracks below are rifts not of the ground but from a dimensional shambler itself.

But since 1994, Doom mapping has grown into a specialty craft. The well of knowledge about how to paint a gorgeous scene, or how to wire up combat that pleases spoiled players, has been filled and deepened and refilled many times over. One needn't bring up the Sunlusts or Counterattacks of the world to cast SIGIL's faults in relief. Smaller-scale auteur masterworks by @mouldy, @yakfak, and @years, and well-crafted id Software ghost-echoes by @Alfonzo, @Pavera, and @Marcaek, show that SIGIL's pure craft is a cut or two below what would win it a Cacoward this season, even with throwback appeal in mind. Implementation can lag behind concept. In the heat of battle, Romero relies for danger above all on the environment and resource balance—on paper, a fine and fitting choice. But too often, when the environment relents, when armament is restricted, the action lapses into the static grind of the Ultimate Doom's roughest patches: chewing through harmless pinkies and cacodemons, cleaning narrow hallways. This is where Romero's task was toughest, and how SIGIL is most apparently retrograde; finessing tension from restriction so steadily, without a lapse, requires a finger on the modern player's pulse. The closer also disappoints, dumping spider and cyber unceremoniously in a glorified tunnel. The original game's final encounters lacked in difficulty, as judged by future generations, but not in theatrics.John Romero has hinted at a Doom 2 release as a followup. We're looking forward to that. The expanded cast is, simply put, a lot more flexible: so many possibilities are unleashed by the new projectile shooters, the pain elemental, the chaingunner, and the flame boi. The Living End is universally regarded as one of the strongest, most iconic maps from the original games—so think of what might rise from the abyss after a quarter century of hibernation.

- @rd.

-

Doom 3 non-BFG Edition + Resurrection of Evil

"Your home for Doom news, information, and development," was the official motto of this site since its inception. Along the way we’ve embraced our step-brothers and sisters—Hexen, Heretic, and Strife—even awarding mods for these games in past Cacowards. But despite the love for our extended family, we have maintained a decidedly old-school approach to the Doom series. While Doom 2016 was being heralded as the great return of the franchise, this community was fawning over Ancient Aliens and the return of John Romero with Tech Gone Bad. We consciously chose to ignore all projects that were not based around the id-tech 1 engine…but we couldn’t live with ourselves had we ignored Team Future’s Phobos.

Created for Doom 3, the bastard child of the Doom franchise, Phobos has deep roots in the classic Doom community. The brainchild of longtime member @Shaviro, Phobos picks up where Team Future’s seminal RTC-3057 left off. It was clear from the first episode of the unfinished trilogy that Shaviro had big plans for a narrative-driven story that was decidedly "not Doom," but the technology just wasn’t there to properly build his vision. With the release of Doom 3, Team Future had the engine they needed to create a truly cinematic Doom project. For the next decade the classic Doom community followed their progress and the yearly updates on the Doomworld forums.

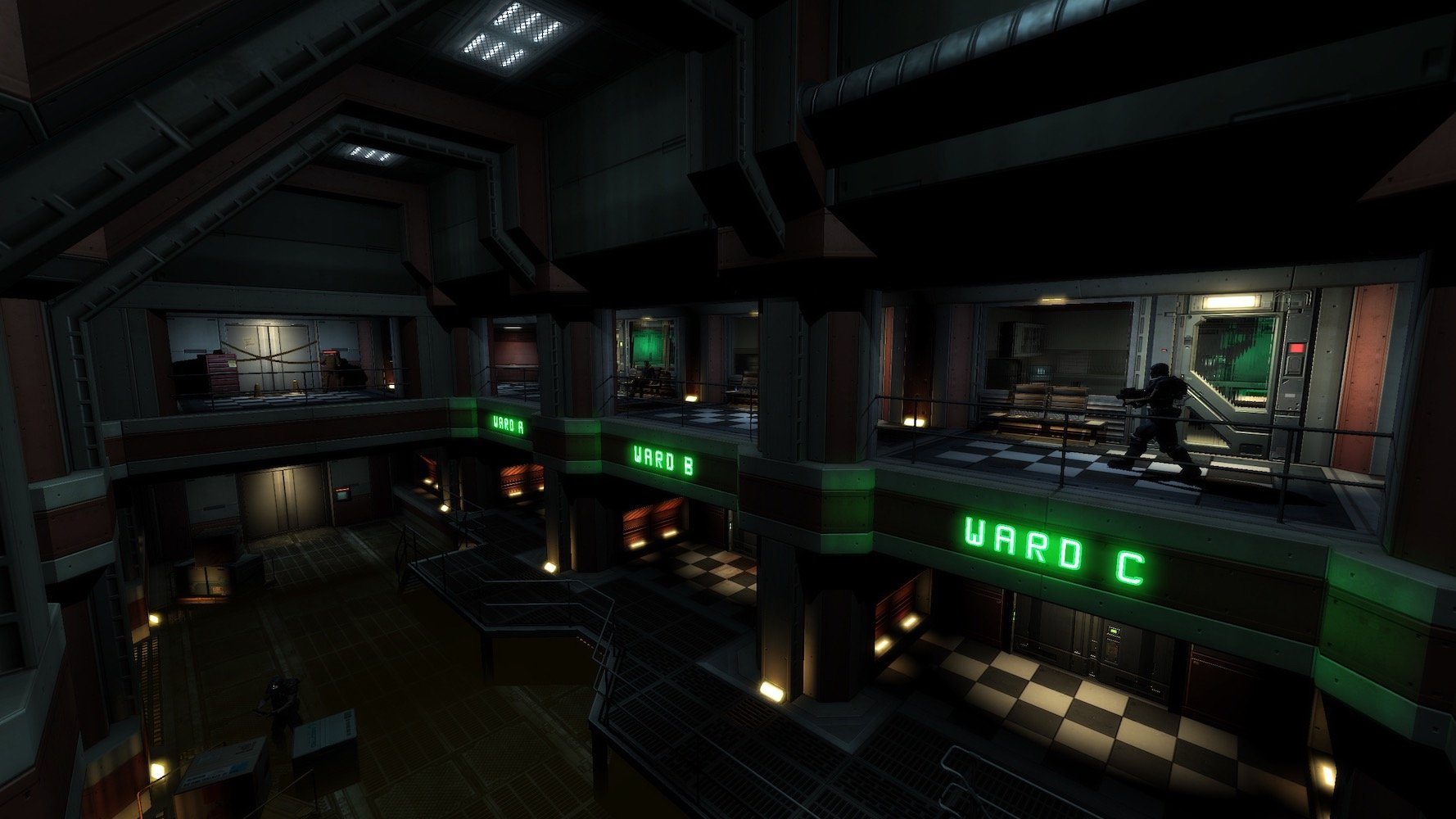

Phobos isn’t just good, it’s downright professional. There’s no hyperbole in arguing that, had Phobos been released as a commercial expansion pack for Doom 3, it would rival the quality of Resurrection of Evil. Phobos’s story begins with a young man sneaking out late at night to rendezvous with the girl next door in the most decidedly un-Doom gameplay you could imagine—think Gone Home or What Remains of Edith Finch. It’s an entertaining change of pace that attempts to build a narrative around the player before he finds himself slaughtering demons in Mars City, which is now a fully realized environment complete with living quarters, neon advertisements, and a sense of scale that was sorely missing in the original retail release.

id Software has long recognized the failures of Doom 3 and tried to rectify them in the BFG Edition by brightening the maps, adding more ammunition, and providing the player a shoulder-mounted flashlight, but none of these fixed the fundamental problem of Doom 3’s mechanics. Complementing Phobos's walking-simulator narrative is a complete overhaul of the base gameplay; gone is the Doom 3 shotgun, replaced with a variant consistent with classic Doom, as well as the elimination of stamina, allowing you to move at top speed indefinitely. These changes make Phobos feel decidedly more RTC-3057 without losing the core of what makes Doom 3 unique.

So why a special mention? Phobos is essentially the only Doom 3 "TC" in existence and, with Team Future’s deep ties to classic Doom and its community, deserves attention and accolades for what it has accomplished. If the Cacowards had snubbed Phobos for its distinct lack of classic Doom, there is quite literally no remaining Doom 3 community to celebrate what Team Future has accomplished—classic Doom fans are the audience for this project, and Shaviro’s history is evidence of that. If Phobos’s three episodes end up being the only mods ever made for Doom 3, it was worth the wait.